NOTE: SPOILERS for both The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and its sequel, Tears of the Kingdom, appear beyond this point! Same goes for Freemasonry.

Happy Lunar New Year!

Today is the last day of the Year of the Water Rabbit and the New Moon will be this afternoon here in Texas. Tomorrow will be the first day of the Year of the Wood Dragon.

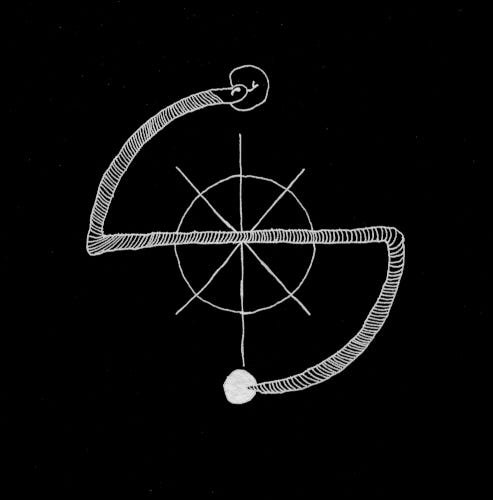

The last “Dragon” year fell in the year 2012 on the Western Calendar, which was the year I performed my major Self-Initiation ritual around the time of my Saturn Return. I wrote an account of that ritual in the post Ten Years Gone for those who are interested; that ritual resulted in the “VSigil” which is featured in the graphical artwork for this site, as well as the avatar when I am writing under the name Dan de Lyons. However, since this post will center on my work with video games, it will be filed under the dual categories of World of Ruin and Word of Hermekate, and I will be using the “mask” of Gogo Bordello for my pen name instead. This serves symbolic purposes, not unlike the way members of a Masonic Lodge regularly change positions to serve in different “offices” in their ceremonies. This will be relevant today, because I will be touching on the overlap between Freemasonry and the Legend of Zelda games Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom in terms of how they relate to the Word of Hermekate.

The timing of this post could not be better, especially given the Hermekatean theme of bridging “East” and “West,” because I happened to finish my playthrough of Tears of the Kingdom on Western New Year’s Day. This convergence was unplanned; I was going to write this post today anyway, but wasn’t thinking about the proximity to the the Lunar New Year until I was reminded this morning.

I love this shit.

In the previous post, I wrote about some of the methods I used to try to “kick-start” the “sprouting” of the Word of Hermekate, because I’d carried it around as a “seed” in my head for several years but was having a hard time developing its meaning. I also wrote about the small circle of friends I had gathered to share what little I did know at the time about it. One of the friends I shared this with was a player of Breath of the Wild, and she asked me once if I had ever played that game, telling me that I should. As I look back, I think it’s probably because of how closely some of the artwork in the game resembles the above-mentioned VSigil:

Also, I had developed the concept of The Personal Myth by that time, and it was already on my to-do list to play Skyward Sword because the opening scene of The Wind Waker was one of the inspirations behind The Personal Myth in the first place:

So that explains the context in which the following took place:

I describe all of this in much greater detail in the post Cornerstones (including a showcasing of all of the relevant artwork), but one way I thought of to generate some inspiration regarding the Word of Hermekate was to check out MidJourney and simply use the word itself—just plain “hermekate” and nothing else—as a prompt, and see what came up. I had a feeling, since I already took so much inspiration from Don Webb’s work, that his brainchild, XaTuring, might help. To make a long story short, the images that resulted all reminded me very strongly of The Legend of Zelda.

So this became my first big clue that The Personal Myth was likely a major component of the Word of Hermekate, and it’s what made me finally decide to drop the money on a Nintendo Switch so I could play Breath of the Wild. The rest, as I’ve written quite a few posts about under the tag World of Ruin, was history, and I soon found myself playing a special, magic(k)ally consecrated, “Self-Initiatory” playthrough of Breath of the Wild. As I’ve discussed in those writings, much of the theory behind the playthrough was drawn from my experience with and understanding of Masonic ceremony and its role in Initiation. For the first time, I will now explain this theory in detail.

Digital Initiation Theory

What is the point of Freemasonic ceremony? What goes on in a Masonic Lodge and what does such activity accomplish? Before I touch on that, I should point out that I was a member of a Co-Masonic Lodge—one which initiated both men and women (one of the places where I can look back on my life and see my Word reflected, as discussed in the previous post)—and that my Lodge would be considered “clandestine”—that is, “unofficial” and thus invalid—by most Freemasons who were Initiated in a Lodge chartered by the Grand Lodge. Aside from the gender equality practiced in Co-Masonry, one other way in which it’s different is that the Lodge gives particular emphasis on teaching the esoteric meaning of Masonic symbolism. As I was given to understand, most “masculine” Lodges don’t really go out of their way to do so; they sometimes have libraries of books that do examine such subjects, but also leave it up to the individual Mason to engage in such study “by their own lights.” I may be wrong about that, but that’s what I was taught.

A Masonic initiation ceremony is essentially a “mystery play” in which the candidate being initiated plays a more or less passive role while the various officers of the Lodge all have important parts in the play. The purpose of the ceremony is to reveal various symbols and convey certain ideas through the words and actions of everyone involved in the ceremony. Some people hold that the results are entirely psychological, and others (such as the Co-Masonic body under which I was initiated) hold that very real, spiritual forces are summoned and brought to bear upon the candidate. In my own Lodge, this was taken so seriously (or should I say “Sirius-ly, since my Lodge was called “Sirius Lodge?”) that the candidate had to be stripped of all metallic objects, including necklaces, earrings, and even piercings, or else the metal would “ground the charge,” rendering the entire ceremony invalid. I was told the story many times of when an initiation had to be performed all over again after it was discovered all the way at the end that the candidate didn’t listen and left their tongue ring in.

However, I will focus here on the psychological aspect of the ceremonies. To make a long story short, due to various factors (which I will discuss forthwith), the ceremony makes a very strong impression on the candidate’s mind, planting symbolic seeds that take root in their psyche and subtly develop over time, particularly as the candidate goes on to engage in Masonic study and reflection upon the symbolism involved.

It is all about the intensity of the experience, and there are a couple of factors that make it as effective as it is:

Masonic secrecy. One of the main reasons for Masonic secrecy has absolutely nothing to do with the Mason gaining dangerous knowledge or being let in on a global conspiracy or any such thing; it has an eminently practical purpose: Masonic ceremonies work best when the candidate knows nothing about what they are about to experience. It’s best if they go in fresh. If they read about the ceremony beforehand, the experience will not be new to them and the ceremony will not make the same strong impression that it can make otherwise. In other words, NO SPOILERS!

Emotional charge: The psychological impact of the ceremony is also enhanced by the heightened emotional atmosphere. Some of this is drawn from the aspect of secrecy mentioned above, but there are a couple of other layers added. One is the aura of prestige surrounding Freemasonry: Even though there are usually Lodges in just about every town (at least in the U.S.A.) and it’s actually a fairly run-of-the-mill thing, it’s also not exactly as mundane as going to church every week: People are proud of their Masonic affiliation, some of them getting bumper stickers or emblems to put on their cars, logos printed on their checks, etc. The ceremony has a greater impact because the candidate is becoming a member of a group that is either held in esteem (by those in the know), or regarded with fear (by conspiracy nuts). In addition to this, there is often a layer of foreboding involved: Even though it’s pretty obvious that they’ll be alright, since everyone involved in an initiation ceremony has made it through the ordeal themselves, an aura of shadowy uncertainty and great expectations is cultivated by other Lodge members leading up to the ceremony itself. I won’t go into details, but there is even a part just before the ceremony itself that can be especially “ominous” to the candidate. Comments will be made here and there about how the experience is “something else” so that the candidate is unsure just what to expect, but is given the sense that it’s something extraordinary.

As a result, the ceremony ends up being a rather emotional experience that does leave a very strong psychological impression on the candidate.

The basic concept of “Digital Self-Initiation” is drawn from this, which means it comes with some caveats; my own experience in Zelda carried some of the same associations as the Masonic initiations I myself had already been through, and even after being “primed” about that aspect, say, by having read my writing about it—if a person tries it without having the same experiential influences I’ve had, the impact will not be the same.

This doesn’t work simply by playing the game; the context is important, as is the mindset of the gamer. For this to work, it has to be approached with reverence and a sense of the sacred—otherwise, it ends up being just another gaming session.

For me, all of this was accentuated by the fact that I was still in the Theater of the Word when I did this, and so the same uncanny, seemingly tailor-made synchronicity that had overtaken the rest of my life also bled into the game (I give a great account of this in the post The Wisdom Eye, which happened to involve in-game symbolism that was itself very Masonic in nature). There were times when it almost felt like the game Breath of the Wild was literally built just for me to have the experiences that I had within it.

Still, even without the specific associations drawn from past experience, these two games in particular—Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom—are really something special. The experience has its own elements of emotional charge that are pretty closely related to those involved in a Masonic initiation and this is especially true for long-standing fans of the series who are playing these games for the first time. Like a Masonic ceremony, there is a very special and impactful aspect to one’s first playthrough that simply isn’t there for other playthroughs, one that is best enjoyed by a person who has had very little of the game revealed to them in advance. Much of this has to do with a sense of discovery; the land of Hyrule was designed meticulously with the player experience in mind, its very architecture completely molded around the first-time experience of a new player of the game. Just as in a Masonic ceremony, where every word and symbol is meant to convey something very specific to the candidate, every mountain, tower, river, tree, and stone in these games was designed and placed with absolutely perfectionistic and palpable purpose.

As I will explore in the next section, I do not think this was by accident…and I am not the only one!

Eastern and Western Esoteric Themes in Zelda

As I’ve alluded to by the inclusion of a video of the intro scene for The Wind Waker (I always loved the living, speaking red lion boat in that game, by the way; always made me think of Ilyas, and gives me a big chuckle now as I write this post on the eve of the Year of the Wood Dragon), it seems to me that the developers of Zelda games have always made a fairly conscious synthesis of mythemes in their games, and by the very nature of these games, they are exemplary of that element of the Word of Hermekate as well as The Personal Myth.

To summarize, the Personal Myth postulates that we each carry our own very personal and unique inner mythic landscape, which I recognize as being drawn and synthesized from familiar myth, foreign myth, and popular myth.

In a nutshell, that’s pretty much what the Zelda franchise does: You have a team of Japanese programmers making games that they know will be largely marketed to a Western audience, so in addition to native mythemes (or, from their perspective, “familiar myth”), they draw a lot of their inspiration from Western myth and fairy tales (or, from their perspective, “foreign myth”), to craft a modern video game that will be played and loved by millions of people for entertainment (or “popular myth.”)

One of the first instances of this that I recognized was in The Ocarina of Time, the first fully-3D Zelda game made for the Nintendo 64: In that game, Link eventually gets a horse to ride around the map, which was very large for its time; that horse is named “Epona,” which is the name of a Celtic goddess of, among other things, horses—one of Her bynames is “The Great Mare.”

The next game, a semi-sequel, Majora’s Mask, was built so heavily around concepts drawn from esoteric Buddhism that one YouTuber made a whole video about it:

However, since this post is focused on how all of this relates to the Word of Hermekate, there’s another set of examples I’d like to point out. While the themes of “Eastern/Western” synthesis and the Personal Myth already come together so nicely here, there’s one more element that appears spread throughout the game that I mentioned as central to Hermekate in previous posts: The phurba.

My first glimpse of this came early on in the game, after the opening section on The Great Plateau. Scattered throughout the game are horse stables, where Link can board his horses when he isn’t riding them. The first one I came across was Dueling Peaks Stable, and the guy standing behind the counter looked very familiar to me:

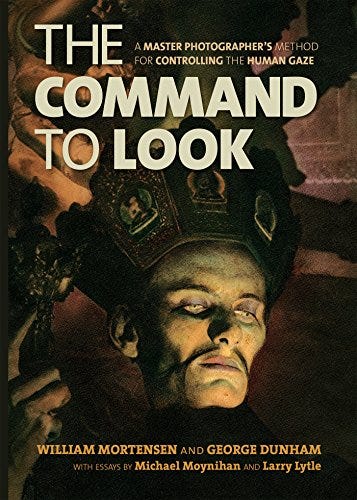

Take a close look at him, especially his hat, his facial hair, and his intense eyes. Now check this out—a reference that resonates here on several different levels at once:

The image on the cover of this book is entitled Tantric Sorceror, and it’s an image I was already quite familiar with owing to my fascination with phurbas (one of which the sorceror in the image is actually holding in his hand off to the left).

This also resonates because some of the core theory from this book was most assuredly used in the meticulous crafting of the game that I described above. The book explores the theory of how to direct the human gaze, and prominent monumental architecture such as the towers and temples that appear in this game are a big part of that. When I saw this guy at the stable, I was sure this was an easter egg the developers included because they may have drawn so much from the theory in this book.

This is also interesting in light of the Satanic and Setian contexts I have been drawing from here in this post, because my knowledge of Words came mostly through the Temple of Set’s work; this book’s theories were also a point of fascination for Anton LaVey, who incorporated photography and particularly the work of William Mortensen in his magic(k)al work. This book is still eagerly read by many Setians today. It’s referenced in Toby Chappell’s book Infernal Geometry and the Left-Hand Path: The Magical System of the Nine Angles.

Of course, these horse-keepers also bear a more direct tie to the book I mentioned in the previous post, A Story Waiting to Pierce You: Mongolia, Tibet and the Destiny of the Western World: From their horse-centric culture to their garb and their status as nomads, the people who run these stables are clearly modeled after Mongol nomadic tribespeople.

Another way in which the symbolism of phurbas was subtly incorporated into the game also serves as yet another example of the synthesis of Eastern and Western mythemes by the developers. A constant recurring element in Zelda games is The Master Sword, “The Blade of Evil’s Bane” or, as it’s known in Breath of the Wild, “The Sword That Seals The Darkness.” It is fairly easily recognizable as having been inspired by the tale of the Sword in the Stone from Arthurian lore; in the legends of King Arthur, only the rightful King of Britain can pull it from the stone, and likewise, in Zelda lore, only Link can remove the Master Sword from its pedestal.

However, this, too, can be read as a reference to phurbas; in some cultures, phurbas are used for healing purposes and in exorcism ceremonies. They are reputed to have the power to ward off evil spirits; and in Vajrayana Buddhism in particular, they are traditionally kept in triangular pedestals—just like The Master Sword.

Last but not least—I couldn’t believe how long it took me to notice this—while phurbas come in many forms, by tradition, the most sacred and holy of them feature a horse motif on the pommel. Well, just before the events I covered in The Wisdom Eye, I had stopped at Riverside Stable (also notable in that the town of Riverside has direct ties to all of this, which is something else I covered in Cornerstones) to view the last of Zelda’s memories I needed to collect for the quest Captured Memories. It was on that visit, just as I stepped out of the nearby Wahgo Katta Shrine (the nearest teleportation point to the area), that I finally noticed: The stables themselves are directly modeled from the pommels of phurbas. Once I saw it, I could never unsee it, and I just can’t believe this was done by accident:

As you might imagine, taking all of this in while playing a game that I already felt was connected on deep levels with the Word of Hermekate was a uniquely moving and powerful experience for me.

Like I said, there were times when it felt like this was all made just for me.

Just to review some of the Masonic symbolism that also found its way into this game, there is the beautiful example of the game’s opening on The Great Plateau, which I wrote about in The Four Gifts of The Great Plateau (and I always chuckled at its title, because when I was going through all this, I had hit a serious “plateau” on my spiritual path and in my life in general). Basically, I hold that The Great Plateau itself is analogous to the 1st degree (Entered Apprentice) ceremony in Freemasonry: You’re isolated on this plateau, learning how to play the game, going through a series of trials administered by The Old Man, each of which awards you with a “Rune,” or a special ability that you will need to use all throughout the game. I began to view that very much as the game’s version of the candidate’s reception of “The Working Tools” in a Masonic ceremony. Finally, after all is said and done and Link is given the paraglider so he can safely leap off of the Great Plateau, there is an obviously-marked jumping-off-point flanked by winged statues on the northeastern-most point of the plateau; and, of course, as Masons know, at the end of the Entered Apprentice ceremony, the new candidate is seated in a chair in the Northeast Corner of the Lodge.

All told, there is so much symbolism like this scattered throughout the game that I was sure while playing it that the developers were quite familiar not only with well-known mythemes, but also with some pretty deep esoteric teachings, and that these were being incorporated into these games in very deep ways. I saw lots of Jungian symbolism in the game, as well, in particular the way the map of Hyrule is arranged, with the story objectives scattered around the edges of the map and Hyrule Castle, shrouded in dark, shadowy energy—placed at the very center of the map—being the final destination. The whole thing struck me as one giant “labyrinth,” with the game itself representing the journey to its center, or metaphorically, the journey to the center of the Self. After such a journey, the final battle with Calamity Ganon, the game’s dark villain, becomes a symbol for Shadow confrontation.

Of course, I wasn’t done then. As was suggested by the images generated from the word “Hermekate” in MidJourney—one clearly “wild” and wooded, and another including imagery reminiscent of walls, i.e., “kingdoms”—it was hinted the entire time I worked through Breath of the Wild that I would not be finished with this work until I played through Tears of the Kingdom as well.

As soon as Tears of the Kingdom was released, I could tell from the screenshots of the game that suddenly flooded my News Feed that the second image with the stone archway is highly reminiscent of the many Sky Islands dotting the sky in that game.

Though I have a separate post (perhaps more than one) planned to focus more specifically on the symbolism in Tears of the Kingdom, one thing stood out that seemed to carry on the Masonic themes begun on The Great Plateau in Breath of the Wild.

In the opening of its sequel, Link and Zelda journey deep underground into secret chambers beneath Hyrule Castle, where they eventually encounter the mummified corpse of Ganondorf—the human man who became the Calamity Ganon that served as the main antagonist in the first game—and emanating from the disembodied hand of King Rauru that grips Ganondorf (though we don’t know that at this point in the game) is a spiral of green light.

To a Masonic eye—especially after being primed to go looking for it with the theory that the opening sequence of Breath of the Wild was analogous to the 1st degree of Entered Apprentice—this spiral suggests the Spiral Staircase visible on the Tracing Board of the 2nd degree, that of Fellowcraft.

Double warning: MAJOR spoilers for Tears of the Kingdom ahead. Do not read further if you intend to experience the game with fresh eyes.

As I said, there is much more to explore from this game in a dedicated post later on, but there turned out to be something very powerful and moving about the way the game ended, especially since I first began this Initiatory journey through Breath of the Wild around the time of New Year’s in 2023; I managed to complete Tears of the Kingdom in the wee hours of New Year’s Day 2024, and the final battle contained a wonderful surprise that reflected not only the upcoming Year of the Dragon, but also the Hermekatean theme of equality and re-imagining gender norms in magic(k):

It’s long been a bone of contention that these games are named after Princess Zelda, but the player actually controls Link in a quest often revolving around rescuing Zelda, the “helpless Princess.” Well, things are different in this game (although this is a major spoiler). Zelda plays a much more active role in the storyline. While Link is doing his thing in present-day Hyrule, he goes about the Kingdom collecting memories (again) of Zelda’s time in the distant past (she gets warped there soon after the scene above with the mummy of Ganondorf), where she was working hard from her end to set up events so that Link could succeed in his work thousands of years later. It turns out Zelda had been flying around overhead in the present the whole time, as she sacrificed her individual personality to become the immortal Light Dragon.

During the final battle, Ganondorf does much the same, transforming himself into Demon Dragon Ganondorf—and Zelda swoops in to help Link fight him.

It was amazing, and I had tears welling up as I played it.

Happy New Year! May the Year of the Wood Dragon bring you happiness, growth, and prosperity.