Final Fantasy VI: The Machinery of Oppression vs. The Magic(k) of Liberation

Exploring the game that introduced a generation to JRPGs and liberatory politics

The occasion of finally sitting down to write this post is bittersweet, to say the least.

As I’ve mentioned many times, the deepest roots of the Substack Dark Twins are in a former Wordpress blog called Gogo’s World of Ruin, which I now write as a subcategory of Dark Twins (and to allay any confusion, while the authorship of different posts is attributed to either Dan de Lyons or Gogo Bordello on this Substack, these are both just different pseudonyms used by me; don’t overthink it, it’s kind of like MF Doom, you just gotta roll with it).

Aeonic Shades

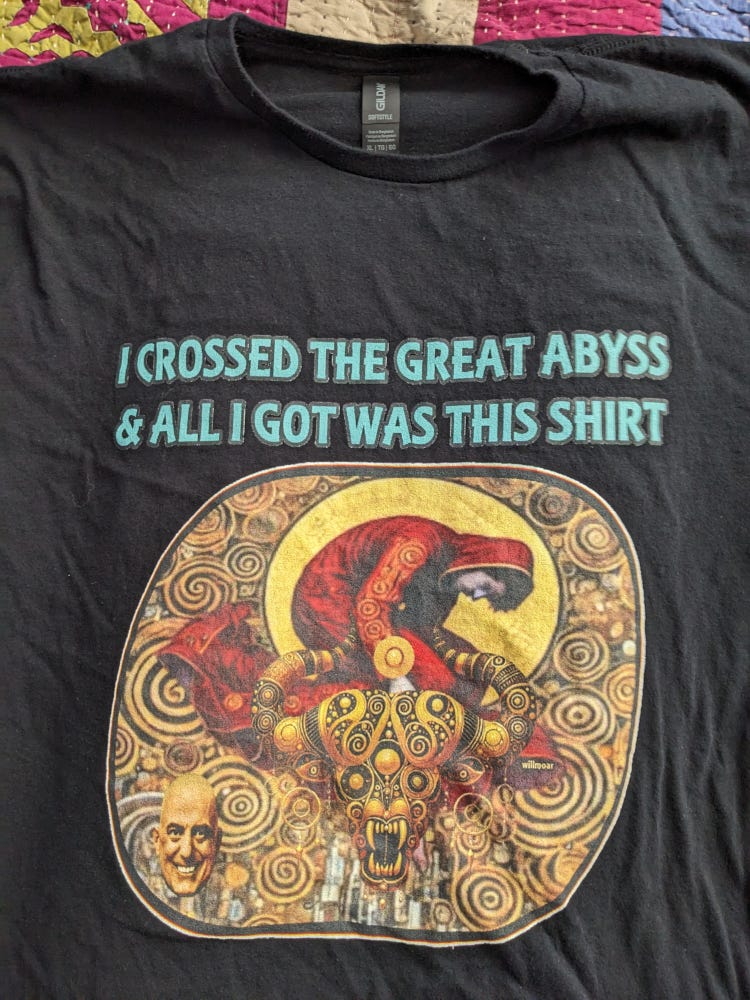

I didn’t realize it when I started writing Gogo’s World of Ruin at the tail end of 2022, but I was in the middle of the Initiatory ordeal known as Crossing the Abyss at the time, on the verge of becoming fully conscious of the fact. As I look back, I can see this reflected in my writing at the time. It became necessary for me to “split off” or compartmentalize the different aspects of my esoteric writing, and ever since about the beginning of 2023, the main focus was soon upon the tarot working I did to help myself across the Abyss—which I covered in the series Turning Things Around: The Inner Tarot Revolution. I finally finished that up back in May. As this Initiatory, tarot-based Shadow work unfolded, I began to consciously develop the Word of Hermekate, and this is one of the main cases where I can see my Initiation bleeding into my writing in ways I couldn’t even see at the time.

Very soon after beginning the blog, my focus was forcefully “hijacked” by my mysterious adventures in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, but it had always been my intention (as fans of the game would be able to guess from the name of the blog itself) to spend plenty of time examining the symbolism and meaning that stems from the SNES game Final Fantasy VI. Why?

Among other reasons, it’s because of how strongly I associate my first magic(k) teacher with that game. I tell the tale of my Initiation into magic(k) at his hands in the post The Wind Rose, but in short, I’ve made a lot about the lessons he once taught me over sessions of FFVI. In truth, a lot of that was romanticized; it’s not so much that he actively used the game as a vehicle for teachings as it is that we spent a lot of time talking magic(k) while he played the game. As fans know, it’s a pretty grindy game depending on how you play it, so we had a lot of time to talk about various things while he was trying to win a weapon at the Dragon’s Neck Coliseum, hunting for Rages on the Veldt, or flying around in the Falcon, the game’s iconic endgame airship, looking for Doom Gaze.

As such, I’m aware that most of the “sage lessons of my teacher” that I associate with the game are more like the magic(k)al insights that I see in the game myself, because of my relationship with him. They are reflections in the game of my memory of a person who dramatically influenced the course of my life. They are my own, personally-constructed nostalgias, and to be quite frank, he probably owns very little of it in the end except for the considerable power of inspiration that my memory of him continues to hold for me.

Further, I know that on some level, the meanings I read into all of this are also my own. I have memories of things said to me by a veritable child back in the mid-90s that have remained meaningful to me over the years, probably for reasons having very little to do with his intentions in telling me about them. I speak mainly, of course, of the “spiritual war” he once warned me about. He was short on details about this, of course—and for all I know, it was complete fantasy on his part—but nonetheless, the idea stuck with me, and I also couldn’t help but notice how the theme of a similar war runs through the story of Final Fantasy VI.

To put it in terms a modern ceremonial magician may or may not readily understand, I think the story and game of Final Fantasy VI are in pretty firm touch with Aeonic currents and are reflecting them in interesting ways. I have not re-published the “About” page from Gogo’s World of Ruin ever since porting the posts over to Dark Twins, but here is an excerpt from the main section:

When Aleister Crowley declared himself the herald of the Aeon of Horus (which, not inconsequentially, was only the most audacious feature of his theory of the Aeons, which rather unilaterally imposed a developmental scheme upon human history that is now impossible to shake), it cast tempestuous waves of consequence across the globe. Like most such globally influential innovations, many of those consequences can be regarded as a form of progress, many can be regarded as regrettable but necessary, and despite the grandiosity of Crowley’s intentions, most of them were unforeseen. However, one ironic consequence—I am now certain of it—is that it resulted in a world in which children literally teach other children magic. While there’s oh-so-much-more to the symbolism of the Child as understood by Crowley than this, it’s like some kind of cosmic joke that it came true in such a literal way. This might sound whimsical, conjuring images of Peter Pan and Tinkerbell, but let me assure you that introducing magical practices and ideas to the still-developing mind of a child can be a disaster when unsupervised; as we will explore sooner than you think, it’s just like handing a kid a match and telling them to go play with fire.

Why am I saying this? Because I was one such child, taught magic by another child in the best way a child knew how, and while I've spent much of my life feeling like one of the most blessed people on the planet for learning what I learned so early, I've also spent much of my life feeling like one of the most cursed people on the planet because of some of the processes bigger than me, and bigger even than magic itself, that have shaped my life as a result. I've spent most of my life feeling very lonely because of what I was handed to carry at such a young age, by someone who wasn't even old enough to comprehend what he himself was putting in my grip. There was a time when it was oh-so-unique, but as magic is further commodified, further popularized through widespread dissemination in media both centralized and social, once more we are seeing waves of consequence reverberating throughout the Aeons: Simplification, efficiency, streamlining of magical ideas, freer exchange of magical technology, and increasing de-mystification are all good things in many ways, but none of this changes the fact that the territory of magic is fathomless, chaotic, and yes, still unavoidably mysterious no matter how common it becomes; that's what makes it magical.

The evolution of the technology, market, and culture surrounding video games has proceeded along very similar lines to those of magic and the two have much in common. Both are equally the pursuits of well-studied specialists with inside knowledge, and of children. Video games are coded by people who are privy to secrets of creation (computer programming) that have been regarded by more than one programming-savvy occultist as a magic all its own, but are consumed and used often by relative "children" both literal and metaphorical, who have no conception of the wonders occurring through their cherished pastime. Magic is believed in by children as a matter of course until it's conditioned out of them, then taken up again by certain types of humans who notice certain patterns they remember in some preternatural way from their childhoods. Magic and video games are much more deeply connected than they seem. The Wyrd of each domain is inextricably linked, and I think we are only seeing the very first manifestations of an exciting new frontier for magic. I've come to realize I'm nowhere near the first person to see it, either. I'm just the first to make it out from my particular angle, and to see what it means doing if I'm interested in keeping the flame alive (and controlled) for future generations.

Again, I can’t really speak to the influences that went into my teacher’s vision of a looming “spiritual war,” but I know from all sorts of angles how similarly ominous feelings and sentiments have colored the collective emotional and mental landscape of humanity in ever-increasing measure over the past few decades. I know that as I’ve considered the prospect of such a “war” on various different levels, for as long as I can remember, I’ve felt that it would be manifesting in part in the form of social unrest and a corresponding totalitarian flux. Come on, we’ve all felt it for a long time, anyone who’s been even partially awake. It’s visible on many different fronts and expressible in many different terms:

Things are going to get dark.

It’s not something I’m happy about, nor is it something to which I’m fully resigned. I’ve spent most of my life living on the dagger’s edge between acceptance and vigilance on these points. Of course, as magicians, we do the best we can on any given day to create the kind of world we want to live in…but this has been in the cards for a while.

Did my teacher, Matt, see the same things in the story of Final Fantasy VI that I see? I do wonder, but to be honest, it’s been a long time since I even thought it relevant; like I said, he tossed me the ball and I ran with it. I figure I approached the material from my own level, every bit as much as he did, and either way, the connection was meaningful.

Is it only because of the association between my teacher and Final Fantasy VI that the game even hit me the way it did?

Of course.

The question is: To what extent?

Regardless of his intentions or mine, I do feel that the game carries an important message which connects with the excerpt above from the original Gogo’s World of Ruin About Page, and this post will be the first in an ongoing series treating some of the many important magic(k)al and spiritual themes I see in the game. I’ll also be getting around to doing a character profile, in the vein of the one I wrote about Gau last year, for each of the game’s main characters. Lastly, as I recently did with The Hylian Banishing Ritual, I’ll eventually be getting into coverage of practical magic(k)al work drawn from Final Fantasy VI…but I’m still working on that. In the meantime, the character tributes and magic(k)al story highlights will have to suffice.

Final Fantasy VI as Generational Initiation

Warning! MAJOR SPOILERS for Final Fantasy VI beyond this point!

The definition of “initiation” is to begin something. In the case of certain secret societies, this may mean undergoing some ritual and/or being made privy to certain secrets, but usually when referring to Initiation in an esoteric sense, we mean something much deeper: An Initiation of this kind is an event or situation that causes a marked change in one’s entire state of being. It can be said without a doubt that this definition applies to the role of Final Fantasy VI for many American (and European) gamers.

U.S. gamers knew it as Final Fantasy III; Final Fantasy had been released on the NES in 1987, and Final Fantasy IV had been released in the U.S. on the SNES under the title of Final Fantasy II. The games had certainly been around, but they were mostly a niche interest in the States, and the main reason for this is also the reason Final Fantasy VI is so special: While the artwork in Final Fantasy games has always been beautiful in spite of the hardware limitations within which the artists have had to work, the genre was known for being relatively flat, story-wise, and needing considerable filling in by a player with a rich imagination. It was most popular with people who had experience playing D&D, and this included my teacher.

Final Fantasy VI became the “virgin JRPG” of an entire generation of American gamers, mainly because of how it stood out from the crowd. It is difficult to overstate the importance of its influence, not only on the JRPG genre itself, but on the entire landscape of storytelling in games.

This is true for three main reasons:

The strength of branding: The Final Fantasy franchise was highly popular in Japan, which drew top talent and artists who were very passionate about their work. Its dealing with Nintendo only served to deepen its popularity by providing it with access to the premier market for video games at the time. The game would never have succeeded without the next two ingredients, but the quality of the game was sold very effectively to an eager U.S. audience through advertising and journalism.

Amazing storytelling and character development: Far from any sort of technical limitation, Final Fantasy VI simply set a new standard for storytelling in the medium of video games. It’s like no one realized what we could be doing with 16-bit graphics and sound because no one cared enough before. The human touch that went into the story and characterization shines through. The story is engaging, timeless, and emotionally potent, and the personality of each character is so well-developed that you really find yourself connecting with them and their motivations. Every character has a well-defined arc and undergoes change from the beginning of the story to the end. The entire world was pretty surprised to see how deeply the human soul could be touched by a simple Nintendo game. This was all accentuated by the third reason for the game’s immense success:

The music. Given the obvious and glaring graphical limitations of the SNES, there’s virtually no way the game would have struck the chord that it did if it weren’t for the music of Nobuo Uematsu. His melodies form the heart and soul of this game, and that includes the characters, every single one of whom has their own personal musical theme.

Prior to Final Fantasy VI, very few American gamers had played an RPG. Now, the opening scene of the game is every bit as iconic to a generation of American gamers as the opening to Star Wars was to a generation of moviegoers; those haunting harps, and the rhythmic stomp of the three sets of MagiTek armor as the gas lights of the mining town of Narshe rise over the horizon? Legendary—and the music is what truly sells it. I still remember the feeling, the first time I heard it, that I was witnessing something meaningful. The music carried the ring of fate in ways I will never be able to describe—and it still does. The imagery carried meanings I could scarcely articulate on first viewing, but which have accumulated layer after layer of unpleasant and somber significance over the years. The game is vividly political from the very first moments.

In a way, it’s always been interesting to me that I was introduced to this game and to the JRPG genre by the same person who introduced me to magic(k), because there have been parallels in my developing understanding of both over time. This means that even though I only knew Matt personally for a couple of years, it’s almost as though he has continued to teach me magic(k)al lessons all these years, via this game.

Aside from the relatively lackluster storytelling in JRPGs prior to FFVI, another reason the genre wasn’t too popular until it came out is that there’s an entire mindset to the whole RPG schtik: All sorts of math and stuff going on in the background/on paper, and for a certain audience, that’s actually where all the real action was.

Like the rest of the mainstream American gaming market to whom this game was sold, a great deal of that stuff was way over my head at first. It’s just…not the kind of gaming I was used to. You know? I grew up on Mario, Zelda, and Street Fighter. That sort of thing. Absolutely everything important that might be going on in those games had clear visual markers and probably auditory ones, too; you’d swing your sword in Zelda and it would hit a skeleton, and you’d hear a little BLOOP, and you could see how much more powerful a new sword was because it changed colors or started flashing or something, etc. These JRPGs were a little more refine than that, and it took some getting used to.

That wasn’t the case for Matt, who was a pretty mean Dungeon Master himself. RPGs were his wheelhouse. So I would do things like spending an entire Saturday throwing myself at Atma Weapon, the boss at the end of the Floating Continent, and getting my ass handed to me before realizing victory—all with the help of a strategy guide—and starting a conversation hoping to relate with Matt about it only to hear him tell me how easy Atma Weapon was.

This meant that he and I were looking at this game and seeing two completely different worlds. It meant there was a lot that I respected about him. It meant that as I learned more about the game over time, my respect for him only deepened even though I haven’t seen him since I was 13; I was still getting to know him better by better understanding a system that mattered to both of us, but for different reasons.

As my understanding of the game led to certain understandings of magic(k), I would look back and wonder if Matt had those same understandings all along; and because humans tend to have a special sort of regard for our mentors, I generally see him in a favorable light as far as such considerations go.

No, I knew next to nothing about this game compared to Matt. I loved the music, and the story really was epic, but I didn’t get the concept of a character class. I didn’t know what all of their stats meant. I would walk into new towns, go to the weapon shop, and blow my money on the weapon with the biggest damage number even though it would actually make my character worse overall, because I didn’t really know how to play the game like Matt did. He was playing chess and I was playing checkers. It really was mainly the story and the hype I had shown up for. I just wasn’t even capable of geeking out to this game on the same level that Matt could, with his understanding and love of all the formulae that shaped the outcomes of the battles I claimed to be enjoying alongside him. Appreciation for all of that would come only years and years later, in retrospect.

So if I couldn’t even grasp the same reality my teacher was blissing out on regularly, what was the attraction for someone like me?

Like I said, that story…wow.

I already compared the opening of FFVI to the opening of Star Wars, and that was no accident because likenesses and references to Star Wars are probably the bread and butter of this game’s popularity, the thing for all of the amazing music and artwork to solidify around. The resemblance of that opening scene to Star Wars was a blatant and loving homage by the developers; the beastlike, lurching advance of the Imperial MagiTek armor across a snowfield recalls the Battle of Hoth from The Empire Strikes Back, and as we eventually see, even the uniforms of the Narshe Guard who respond to defend their town resemble those of the rebel soldiers in the Star Wars film.

The themes are timeless, especially insofar as Star Wars was itself a comment on World War II.

Two of the three MagiTek soldiers are grunts named Vicks and Wedge (also Star Wars references, though botched by a bad translation job). The third is a girl whose name we haven’t yet learned, and she is being controlled by a slave crown that robs her of all personal volition. As we come to learn, the MagiTek soldiers are riding weaponry that is powered by magic, and the girl being escorted by the soldiers has great magical power herself—hence the slave crown, meant to keep her under the Empire’s control. The team of three are advancing on the town of Narshe because something was found there that the Empire wants: An Esper, or a magical being of the kind that the Empire uses to power its MagiTek weaponry.

Final Fantasy VI is a story about oppression and the fight for freedom. It’s about political power and personal power, but the framing of it all within the backdrop of magic simply holds connotations—especially in this day and age, with everything happening in the world right now—that carry special meaning for those who walk the path of Initiation.

The very structure of the game was a strong formative influence on my understanding of magic(k) in ways that are exceedingly difficult to express without going into some fairly meaty story analysis and especially without giving spoilers. The story can be neatly divided into two main sections and is one of those stories that revolves around a surprise false ending.

The game begins in the so-called “World of Balance,” with blue seas and verdant, green plains. Despite indications, however, it’s a world in conflict; the Gestahlian Empire on the Southern Continent is consolidating magically-driven military power and gradually conquering the rest of the world. We are literally watching a magical fascist world takeover in action.

The plot in the World of Balance keeps the player on a pretty firm track with little room for deviation, telling the story of the underground rebellion of the Returners against the Empire; there’s plenty of tension and give-and-take, with the Empire gaining ground here and the Returners making headway there, but everything seems to be coming to a pretty clear resolution. We watch the descent of the game’s villain, General Kefka, into psychotic madness, manipulating events and even the Emperor himself to a climax that feels like it’s about to be a nice, satisfying end to the game; Kefka awaits us on the Floating Continent, held aloft by the power of the Warring Triad, a trio of goddesses who are the source of all magic, and we think we’re going to go up there, defeat him, and save the day.

Instead, we watch him murder the Emperor in cold blood, set the power of the goddesses completely out of balance, seize it for himself, and use it to basically destroy the planet.

Welcome to “The World of Ruin.” Evil has won and the world is a wreck…

…now go find your friends and keep up the fight.

I’m not entirely sure where this new series of posts is going to go, but I know I’m excited to cover the ground I’ve already got planned out. I also know that parts of me are uneasy about what the future holds, and sad to say that the proverbial writing appears to be on the wall: There is meaning in Final Fantasy VI’s tale of power, war, and magic, written in the Twilight Language of living, dynamic allegory and drawn from the deepest currents of the collective unconscious. It’s a map of things to come, delivered to us just in time by the spirit world…

…let’s study it together.