Good evening, readers!

This will be my first paid post since rebuilding Dark Twins. I’ve been stalling long enough and am now diligently working to finish revisions on the manuscript I’ve been talking up so much. I have great news: I’ve completely re-written the Introduction and run it by some friends who matter: The most vulnerable among us in so very many ways. I refer, of course, to transgender people, a community of which I am now a proud member. I have long been inspired by the transgender journey, personally seeing it as one of the most perfect embodiments of the Word of Xeper as I understand it. It is for this reason that I have at times been heartbroken that the path to which I am so deeply devoted is still so unsafe for us.

I aim to change that.

My plan for the past several months has been to finish the Introduction and run it by some friends of mine who have long experience not only in the transgender community (I’ve been…”offish”), but in anti-fascism. Through long discussions, I’m happy to have found some people at last with whom I can see eye-to-eye.

Now that it’s ready, I decided to take a walk on the wild side, turn on paid subscriptions, and see how many people are willing to pay the nominal monthly subscription fee of $5.00 to read it. I have nothing to lose on this, really—and I have a feeling that a lot of people stand to gain a safe space where it’s been slim pickings.

I’ll see which way the wind blows before deciding how best to proceed in publishing the rest of the material.

Thanks to all my subscribers and readers for keeping me going. I’m telling you, my stats may not be stellar, but they are consistent and pretty solid. You all have my gratitude.

Now it’s time to show it.

Introduction

Nothing is as it seems, life is full of surprises, and truth is stranger than fiction.

The above log jam of aphorisms is the most succinct way I can think of to capture the essence of the long journey leading to the completion of this book. As a set of statements, it also serves as an apt descriptor of the Left Hand Path (LHP) as a whole. This convergence will set the stage for the approach I’ll be taking throughout this book, where I will interweave aspects of my own personal journey with a more impersonal, even philosophical exploration of Left Hand Path vices and virtues. I’ll be taking this approach because using my own experiences as examples is the most direct and elegant way for me to illustrate two important aspects of the Left Hand Path that each reflect the other:

The focus, on the Left Hand Path, upon the self and one’s own personal development.

The uniqueness of each individual’s Left Hand Path journey.

The Left Hand Path is probably the most controversial and misunderstood branch of the broader esoteric subculture, which is itself already controversial and misunderstood relative to society as a whole. From the perspective of many occultists, the term “Left Hand Path” covers “black magic,” and thus describes the edgier, darker parts of “occult country,” where necromancy and demonic magic are standard fare; where baneful magic like cursing is allowed and even encouraged; where there are no ethical hangups about magic that is self-serving, aimed at mundane goals, or which attempts to impinge on the free will of others; where all of the usual rules and guidelines shaping magical practice are subverted. Naturally, in this common view, black magicians all embrace a goth or heavy metal aesthetic.

Of course, these are half-truths. Any of the above traits may apply incidentally to any given Left Hand Path practitioner, but the problem with the above view is that it’s mostly constructed from negation, formed by way of contrast with one’s own traditions. In reality, none of the above criteria are definitive of the Left Hand Path, and there are people on the Left Hand Path to whom none of these traits apply. Basically, what happens is that most occultists live by their chosen moral code, and they regard anyone who steps outside of those rules as part of the Left Hand Path because they don’t know any better. Many never go out of their way to learn better because the mindset they are coming from is that “the Right Hand Path is for the good guys, so the Left Hand Path is for the bad guys,” and they have no desire to learn anything about “the bad guys.” There are various ways of distinguishing “black magic” from “white magic,” but a common way of defining the two is simply that “black magic” describes whatever magic is forbidden or discouraged within a given tradition whereas all the acceptable or recommended magic is described as “white magic.”

Muddying these waters even further is the fact that there is no shortage of people who consider themselves to be members of the Left Hand Path who—in a certain misunderstanding—assume these more vague, popular ways of defining the path are accurate, thus reinforcing the stereotypes. Perhaps they’re simply attracted to the dark aesthetics or want to be rebellious, which aren’t necessarily bad motives in and of themselves. This is not a crime, and it is, after all, very much in line with the LHP ethos that people should be free to try things out and explore what interests them. However, some of them do miss the deeper objectives of Left Hand Path practice, engaging at a relatively superficial level and often in ways that serve no real purpose beyond self-aggrandizement. Quite often, these people, colloquially known as “edgelords” in Left Hand Path spaces, are simply attention-seekers. Some (though certainly not all) of them do end up finding their way to more or less sincere and advanced Left Hand Path practice. Others find their way into a pipeline that leads to hateful and oppressive extremist movements. I’ll be returning to this topic because it’s an important part of why I am writing this book.

Evolution of the Left Hand Path

Now that I’ve described some of the ways in which the contemporary Left Hand Path is mischaracterized, establishing what the Left Hand Path isn’t—what, then, is it?

As it turns out, understanding how the contemporary Left Hand Path is defined is a nuanced subject all its own that involves a complex history of the term’s use, which may be one reason the definition is so widely misunderstood; there is great temptation to oversimplify things in ways that render the definition less clear, and as we proceed, it may become apparent how some of the more inaccurate ways of defining the path are a result of blurring the lines between different usages of the same term. The definition has evolved over time, and the term continues to be used in various ways in different contexts, making it difficult at times to be certain of which context is being referenced in a given situation. Understanding the big picture and how its parts fit together is critical to understanding how and why the LHP is what it is today.

For this section, I will be leaning heavily on the book Lords of the Left-Hand Path by Stephen E. Flowers, Ph.D. A full exploration of the nature and evolution of the Left Hand Path is beyond the scope of this work, but Lords of the Left-Hand Path is devoted entirely to that purpose and is widely considered a standard text on the subject. I include this section in case some readers of this text are not familiar with that one, and I highly recommend that anyone with an interest in the LHP read it if they haven’t done so already. The outline I develop here in the introduction will serve as a foundation for my approach to fleshing out the chapters on each of the LHP vices and virtues.

Historically, the first appearance of the term stems from ancient Indian tantra, which was split into two main divisions: Dakshinachara, or “right-way,” and vamachara, or “left-way.”1 Within this cultural context, the distinctions between the two paths can be nuanced, with each branch composed of many different traditions that each hold their own unique perspective. However, broadly speaking, the dakshinachara, which is referred to in English as the Right Hand Path (RHP), seeks to effect a complete union between the individual consciousness and the universal soul, or paramatman.2 In other words, one seeks to cultivate their inner divinity so fully that they give up their individual existence entirely and reunify with the divine soul of the universe. In this sense, the dakshinachara is largely characterized by going with the natural flow, and takes the form of conventional religious practices, catering to social norms, and upholding relatively strict and clear-cut moral codes. By contrast, the vamachara, known in English as the Left Hand Path, reverses the natural flow. It tends toward favoring individual development in ways that are unconventional and which defy blind adherence to social norms. In some traditions, it’s considered an accelerated, but more hazardous road to the same ultimate goal of the Right Hand Path, enabling the initiate to attain in one lifetime what would otherwise take many lifetimes. In some traditions, it also seeks to develop the individual self or jiva to the fullest extent without taking the final step of unifying with paramatman or anything else. Instead, the goal is that of remaining separate and immortal, taking on earthly incarnations only at will (as opposed to being a passive subject driven from one incarnation to another by the law of karma).3 As part of effecting this transformation, practitioners of the vamachara ritually engaged in practices that were forbidden on the dakshinachara and in everyday society as a means of separating themselves from the natural and social order; to differentiate oneself in this way on the earthly plane was the beginning of the same path that leads to remaining distinct and separate from universal divinity at the apotheosis of spiritual attainment.

Tantric lineages continue into the present day, so this sense of the term “Left Hand Path” is by no means anachronistic. In LHP spaces, when the term “Left Hand Path” is being used to refer to tantric practices, it is often called the “Eastern Left Hand Path” in order to specify this.

The term “Left Hand Path” was first introduced into the Western esoteric tradition by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, who co-founded The Theosophical Society in 18754. Blavatsky was almost certainly exposed to the concepts of the Left and Right Hand Paths in her travels throughout India and Tibet. Blavatsky claimed during her life to be guided and led by two “Mahatmas” (“great-souled ones”) or “Masters” named Morya and Koot-Hoomi (or Kuthumi).5 These “Masters of the Wisdom” were said to be members of a lodge of adepts akin to the so-called ascended masters of New Age lore, whose task is to guide and watch over humanity in its spiritual evolution. This Trans-Himalayan Brotherhood was said to stand for the path of spirit, in opposition to a corresponding lodge of “black magicians” called “The Brothers of the Shadow” who walk the path of matter.6 Sometimes, this pair of opposing lodges was described in terms of the Right Hand Path and Left Hand Path, where the Right Hand Path corresponded to the Trans-Himalayan Brotherhood and the Left Hand Path corresponded to the Brothers of the Shadow. Due to the strict good/evil dichotomy involved here, it became commonplace for Theosophists to characterize anyone they disapprove of (especially morally) as being in league with the “Left Hand Path,” if not in fact, then at least in spirit. In broad strokes, the Trans-Himalayan Brotherhood was said to be dedicated to self-renunciation and serving humanity at large, while the core defining feature of the Brothers of the Shadow was selfishness.

After Blavatsky, the most well-known Western occultist to apply the term “Left Hand Path” was Aleister Crowley, and as it happens, there is a great deal of similarity between his application of the term and Blavatsky’s. This is true even though in the sense Crowley applied it, it has a context-specific, technical meaning that would apply to comparably few people. Aleister Crowley formed an initiatory school called the A∴A∴, which is composed of 11 grades (12 if you count Probationer) modeled on the grade structure of another order, The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In the grade of Adeptus Exemptus (7°=4□)—an advanced level—the initiate enters the Abyss, the universal gulf depicted on the Qabbalistic Tree of Life as separating the three Supernal sephiroth from the lower seven sephiroth. Qabbalistically, this represents the division between the absolute, unmanifest state of divine unity (above the Abyss) and the manifest universe of separation (below the Abyss). The Abyss itself is a “void” serving as a liminal space between the world of manifestation and the divine. As such, on an individual level, to enter the Abyss as an Adeptus Exemptus is to become a “separate being from...the rest of the Universe.”7

This was the point at which Crowley made the distinction between the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path; according to him, before this point, the two paths are the same. The ultimate goal at the highest levels of the A∴A∴ system is to aspire to full union with the divine. At this point in the system, that means crossing the Abyss, or fully annihilating the personality or ego that maintains the illusion of one’s separateness from the divine. To do this, in Crowley’s opinion, was to walk the Right Hand Path. By contrast, the “Brothers of the Left Hand Path” are those “who ‘shut themselves up,’ who refuse their blood to the cup, who have trampled Love in the Race for self-aggrandizement.”8 In other words, Crowley defined the Left Hand Path as remaining in the Abyss, continuing to identify with one’s individual personality, and doing one’s own will in resistance to the greater divine will.

There are a number of interesting problems with this definition of terms. This is especially true insofar as they apply to Crowley’s own example as someone who claimed to have made it all the way across the Abyss, to the final grade of his A∴A∴system, that of Ipsissimus (10°=1□). In so doing, Crowley was a “pioneer” of sorts, pushing the boundaries of that which was previously thought possible. In the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, it was generally held that no one still living in a human body could fully cross the Abyss, and this makes a lot of logical sense when the meaning of the Abyss relative to the rest of the Tree of Life is understood in a Qabbalistic sense. If, after all, the Abyss is the dividing line between individual consciousness and union with the divine, how would it make sense for a person to claim a state of divine union while still inhabiting a human body, which unequivocally necessitates that one maintain a functioning ego? Put simply, we need an ego (as the word is used and understood in psychology) in order to function at all in the world. How can one continue to move about, to eat, drink, and shit, fully immersed in the material world of sense perception, if one is supposedly at one with the divine? In theological or metaphysical terms, there are a number of ways of resolving this apparent paradox, but it would seem that prior to Crowley, the solution in Western esoteric circles was to suppose that a state of being equivalent to Adeptus Exemptus was effectively the upper limit of what flesh-and-blood humans could achieve. Given the grounding of Qabbalistic tradition in Judaism, it would seem logical to look to various figures in the Abrahamic scriptures—namely, Enoch, Elijah, and Jesus, who were each said to fully ascend into heaven in a way that involved moving beyond physical existence entirely—and to suppose that something similar would be required in order to fully realize divine union. The philosophy of Aleister Crowley, however, was influenced heavily by Buddhist teachings. There, we have the example of none other than the Buddha himself, who continued to live and walk among humanity after reaching enlightenment. One might suppose that Crowley took note of his example (not to mention that of Mohammad, whose name Crowley invoked in his description of the second-highest grade in the A∴A∴and Golden Dawn systems, that of Magus (9°=2□)) and made some adjustments to his expectations while also maintaining the view that upon reaching such a state, a person must have largely subdued their personality; it would, after all, be the eminently Buddhist way of performing such a spiritual stature.9

The main problem with this model is the very example set by Crowley himself: By most accounts, his behavior after crossing this lofty threshold appeared to be that of a person still very much “encumbered” by his original personality flaws, attachments, and aversions. As Stephen Flowers so succinctly put it in Lords of the Left-Hand Path, “Analysis of his life shows, however, that the personality of Aleister Crowley appeared to be just as strong emerging from the Abyss (on December 3, 1909) as it was going into the Abyss earlier that same year. Of course, our eyes may be deceived.”10 I’ll be returning to the “echoes” of this controversy or paradox (depending on how one looks at it) throughout this book; it may seem like an incidental matter, but we will see how it becomes a foundational part of this book’s message.

Kenneth Grant was a onetime student of Aleister Crowley, as well as his personal secretary for a time. The most notable aspect of his work in the context of this book is that—in a sense, at least—he turned some of Crowley’s ideas on their head by openly embracing the label of Left Hand Path magician. While the “Brothers of the Shadow” and “Brothers of the Left Hand Path” were portrayed as the “villains” of Theosophy and Thelema respectively, Kenneth Grant viewed the Left Hand Path in another light, defining it in very different terms than the ones Crowley used. To Crowley, this was strictly about whether or not an initiate chooses to negate their ego upon reaching the Abyss; to Grant, this was more about a method of practice. In his terms, the Left Hand Path was “the path of those who use the energies of sex for gaining control of unseen worlds and their denizens.”11 After studying Thelema within the original O.T.O., Grant went on to form his own order which he first called The Typhonian Ordo Templi Orientis, but which was renamed The Typhonian Order following a copyright dispute.

In the Typhonian tradition, there is a marked emphasis placed on exploring the Tunnels of Set, or the dark side of the Tree of Life, which holds many frightening non-human denizens; Grant felt it was important to confront and integrate darkness (both outer and inner) head-on in order to develop in a fully balanced way. In some ways, Grant’s perspective regarding the Left Hand Path was much closer to the original tantric meaning of the term than Crowley’s was, and this is why I said above that Grant turned Crowley’s ideas on their head “in a sense.”

To a person who is well-versed in tantra, it is already apparent what was going on with Blavatsky and Crowley alike: They were each viewing the concept of the LHP largely through the distortions of a completely different and in many ways antithetical cultural lens to that of the term’s origin. There is a great deal of nuance in tantric philosophy that does not readily translate into Western terms. Even Grant, whose understanding of the term’s original context appears to have been more accurate, fell victim, to a certain extent, to the common Western tendency to make tantra all about sex. In the cases of all of the figures discussed thus far, there are different ways in which the figure in question was taking a complex spiritual philosophy and “importing” select concepts from it into their own system of thought in ways that were not faithful to the original cultural context. This is often termed “cultural appropriation” nowadays, but that’s a very loaded term that carries a lot of political charge that conflicts in many ways with magickal principles.

Regarding the understanding of Blavatsky and Crowley, there is a grain of truth in their emphasis on the different relationships to the individual self held on the Right and Left Hand Paths, but they missed quite a lot of nuance by breaking the distinction down into such stark, black-and-white, moralistic terms. This, of course, reflects the largely Christian backgrounds of each, in which the entire universe is viewed in morally dualistic terms. It also reflects the Western enshrinement of individualism, even to a greater extent than is encouraged in authentic Left Hand Path tantra. Meanwhile, tantra hails from cultures that are far more collectivist than individualist by nature, and rests upon a monistic rather than dualistic philosophical foundation. In other words, the cultural differences are pretty much literally akin to the difference between night and day. Thus, a certain level of distortion is to be expected. Inevitably, important meaning is lost in translation.

Meanwhile, there is also some validity in Kenneth Grant’s rooting of the Left Hand Path in sexual practices because these are a part of tantric traditions, as is the more direct confrontation with darkness and severity (think of the frightening, wrathful visage of tantric deities, which are generally interpreted as “evil” and “demonic” by Westerners unfamiliar with tantra). However, these are both once again mere parts of the greater whole that is tantra, and Grant’s understanding of the nature of the entities to be found in the Tunnels of Set would likely be challenged by a tantric adept.

To say the least, a dedicated student of tantra would likely regard the above examples of the incorporation of the Left Hand Path into otherwise Western systems as “clumsy” at best, and may use even harsher terms to describe it. If it weren’t for the fact that the term’s use in these venues has likely led many seekers (myself included) to learn more about the authentic indigenous traditions from which the term was drawn, the result would likely have instead been nothing more than to sow great confusion and misunderstanding. In practice, the results have been mixed.

As if the above state of affairs weren’t lacking enough in clarity, the next pivot in the term’s ever-shifting usage in the West blew smoke all over the entire scene. In 1966, Anton Szandor LaVey founded the Church of Satan, which was in many ways a rather “on-the-nose” refutation of conventional religion—especially Christianity. Contrary to popular belief (especially Christian belief), the Church of Satan does not involve devil worship; if Satanism encourages the worship of anyone, it is the worship of oneself as the “god” of one’s life.12

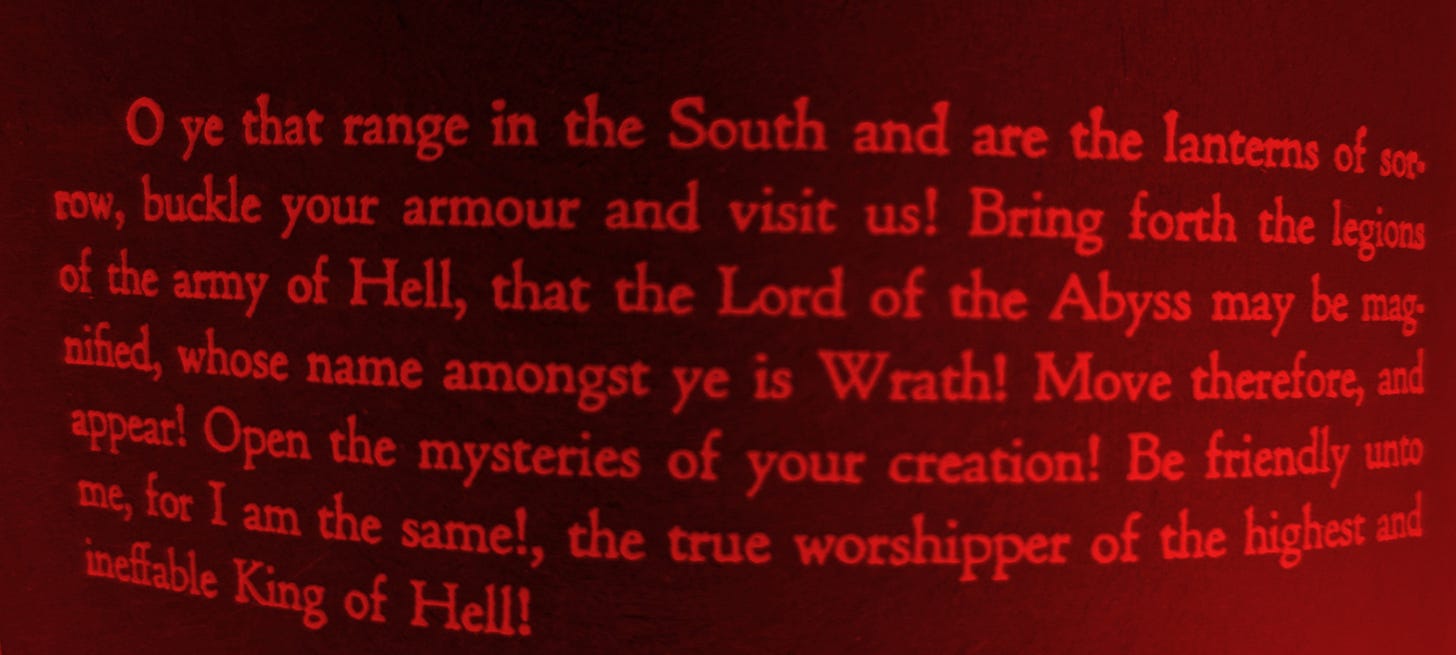

Anton LaVey placed the Church of Satan on the Left Hand Path himself in the very first line of the prologue of The Satanic Bible: “The gods of the right-hand path have bickered and quarreled for an entire age of the earth.”13 It becomes explicit later in the text, if it were not already, that he considered Satan to be “the personification of the Left Hand Path.”14 It is not made apparent in The Satanic Bible from where LaVey drew this nomenclature, but Stephen Flowers does mention in Lords of the Left-Hand Path that Crowley was named as an early influence of his in the biography The Devil’s Avenger by Burton H. Wolfe.15 Further possible signs of this influence might also be LaVey’s adaptation of the Enochian Keys, popularized by Crowley’s The Vision and the Voice, for the final section of The Satanic Bible, along with the fact that the Church of Satan’s degree system seems to be inspired by that used in the A∴A∴. As such, it is reasonable to speculate that LaVey’s use of the LHP/RHP dichotomy comes from Crowley’s understanding of the same. This is especially true insofar as Crowley’s definition of the term boiled down to a synonym for egotism, and glorification of the self is essentially Satanism’s core tenet. As LaVey notes, the word “Satan” means “’adversary’ or ‘opposition’”.16 It was part of his intention, as the spearhead of this new movement, to play the role of villain. He knew that in a milieu shaped as powerfully by Aleister Crowley’s ideas as occulture was at the time, an eager adoption of the label “Left Hand Path” would be perceived by the typical occultist of his day to be just as shocking as his use of the name of Satan was to Christendom. It was very much a conscious part of his bit as a transgressive showman—and it worked well.

As a public figure and spokesperson for Satanism, Anton LaVey was a bit eccentric, and his philosophy can sometimes seem to embody contradiction at first, until one looks closer and begins to understand the logic of his unique perspective: He despised conventional religion, then he founded a religion; he named the religion after a demonic entity, but the religion had nothing at all to do with worshiping that entity. It’s commonly held that he didn’t even believe in Satan’s actual existence, though this is a matter still hotly debated by people who care enough to be invested in the answer one way or the other. It’s notable that in the first chapter of the “Book of Lucifer” section of The Satanic Bible, he approached discussion about God in a somewhat ambiguous way that never actually denies the existence of God, but describes God in terms of an impersonal force in the universe that holds no interest in what any human being does.17 In the next chapter, he proposes that a Satanist should worship the god within oneself.18 Throughout the book, he refers to Satan or the Devil in more personal terms, but also speaks frequently to what Satan “symbolizes” or “represents,” suggesting that he viewed Satan as a metaphor. Interestingly, this contrast between God as an impersonal force and Satan as an individual figure does reflect in intriguing ways the differing perspectives and goals of the RHP and LHP, and I think there may be deeper meaning in this whether or not LaVey intended for there to be.

Whatever his true and most intimate perspective was, the religion of Satanism is overwhelmingly presented as naturalistic and concerning itself mainly with the material world, with the irony being that this was indeed one of the important ways in which LaVey distinguished Satanism from the institutions it was set up to mock. For a proverbial man of the cloth—albeit a dark cloth—the major points of his philosophy were eminently secular. A skeptic by nature, LaVey viewed man as essentially another animal, albeit an intelligent and sophisticated one.19 As such, Satanism stresses indulgence in the pleasures of the flesh, including and especially the ones forbidden by orthodox religion. LaVey demonstrated his keen insight into psychology by observing that it’s the very uptight denial of these pleasures that so often causes the religious to remain so deeply locked in combat with them, controlled by their compulsive avoidance of the same every bit as much as an addict is controlled by their compulsive dependence on their drug of choice. His version of a middle way was indulgence—to let go and allow oneself to enjoy good food, drink, sex, and other sensual pleasures without feeling guilty about it.20

Anton LaVey’s adoption of the term “Left Hand Path” had the result of further reinforcing the way it was defined by Blavatsky and Crowley, however imprecise their expressions of the term were: They were saying there were self-centered “black magicians” out there, and LaVey was basically playing off of that trope and saying, “Indeed there are—and you can become a member of our church!” At the same time, the Church of Satan’s philosophy embodied an intentional excision of any sort of spiritual sense of the term that was present in its original cultural context: Satanism is a religion and philosophy of carnality.

Due to the secular orientation of the Church of Satan, which attracted global attention and some high-profile celebrities as members, the term “Left Hand Path” was pushed into much wider circulation than ever before; The Satanic Bible has sold over a million copies, and everyone who has read it has been exposed to the term. This may be the single largest contributor to the current lack of clarity surrounding its meaning.

Emerging from the environment of the Church of Satan was Michael Aquino, a man who brought a level of philosophical refinement and articulation to the evolving Western picture of the Left Hand Path that enabled him to weave the wayward threads discussed thus far into a coherent tapestry that reconnected the contemporary LHP with some of the principles of its tantric roots, restored much of its purpose, and reclaimed its central imperatives as positive and spiritual values. He did all of this while simultaneously charting a visionary new course that grounded the LHP more in sound scientific principles than had ever been done before, cutting through much occult detritus and accumulated superstition with a refreshingly pragmatic perspective. What he achieved in this direction was nothing short of an alchemical transmutation.

Michael Aquino was originally a high-ranking member of the Church of Satan and a protégé of Anton LaVey. Onetime editor of The Cloven Hoof, the Church of Satan’s official newsletter, Aquino penned some of the ceremonies that appeared in The Satanic Bible’s companion book, The Satanic Rituals. He also wrote The Diabolicon, a “restatement of certain themes” of the poem Paradise Lost by John Milton, only with a more favorable portrayal of Satan and those who followed in his rebellion.21 The poem so impressed Anton LaVey that it resulted in Aquino’s promotion to the rank of Priest of Mendes. Aquino would go on to reach the rank of Magister, the highest degree possible in the Church of Satan other than Magus, which was held exclusively by LaVey.22 In 1975, Anton LaVey announced that the rank of Priest would be conferred in exchange for money or “objects of value,” essentially selling the Priesthood for profit.23

By Aquino’s recounting, this sent tremors throughout the existing Priesthood, and Aquino himself took the decision as a betrayal of the Church of Satan’s principles up to that point. An important aspect of Aquino’s response was also what appears to have been a theological disagreement with LaVey regarding the nature of the Priesthood itself. While Satanism is almost universally recognized as an inherently atheistic “religion” that views Satan purely as a metaphor or symbol, Aquino held that Satan (or an entity who has gone by that name alongside others) actually exists, stating in his book Temple of Set that he “did not regard Anton LaVey as simply a charismatic individual or even genius, but as the anointed personal deputy of Satan himself.”24

In the wake of the announcement, Michael Aquino voiced his protest to LaVey, but was rebuffed. Feeling as though he was left with no other choice, Michael Aquino performed what is now known as The North Solstice X Working on the night of June 21-22, 1975, wherein he wrote The Book of Coming Forth by Night over the course of four hours.24

The Book of Coming Forth by Night was an “inspired” text written from the perspective of that very entity whom Michael Aquino felt was also behind the work of Anton LaVey—”Satan”—only in this instance, the guise was instead that of the Egyptian neter Set. This document became the founding document of a church Michael Aquino would establish in response to LaVey’s decision to put positions in the Church of Satan’s Priesthood up for sale: The Temple of Set. The lion’s share of the Church of Satan’s Priesthood would follow him.

The Temple of Set is an interesting and rather unique school in comparison to the various esoteric orders connected with the figures thus far explored: That is, it holds a handful of basic philosophical principles to be true, but also leaves a great deal of room for interpretation—as well as implementation or praxis—in the hands of its members. However, to begin with, the philosophy of the Temple of Set first establishes its cosmology, which is dualistic in nature: There is the Objective Universe (OU), or the natural, physical world described by Aquino as “a single assemblage of matter/energy [balanced cosmically by an equivalence of antimatter and antienergy].”25 This is the external universe which we all share while living within physical bodies. Then there is the Subjective Universe (SU), which Aquino describes as “each self-conscious being’s perception of the OU, blended with personally-generated overlays, selective impressions, and creative imagination as instinctive, indoctrinated, inspired, and/or initiated.”26 In other words, it is the universe as each individual experiences it. It’s a deceptively subtle point of the Temple’s dualism that each individual has their own Subjective Universe and that each SU is a “universe” in its own right, not simply consisting of the impressions made upon one’s consciousness by the OU, but existing beyond and apart from it. The contrast between the OU and one’s SU is thus analogous to the contrast, in ancient Hellenistic thought, between psyche (SU) and physis (OU).

This cosmology dovetails with the Temple’s theology, especially that surrounding the neter of Set. While Michael Aquino felt that there was a real entity behind and indwelling the symbolic figure of Satan, he also thought that Christian theology was woefully insufficient in terms of explaining it. For these purposes, he felt Egyptian religion held much clearer answers, and that in Egyptian religious terms, the figure most closely corresponding with the Christian Satan was that of the neter Set, around whom much confusion swirls (which is rather befitting his nature). To the Egyptians, all of nature is alive and willed into existence by the neteru, reflected clearly in the fact that the very word “nature” is derived from the term “neter.”27 “Neteru” is the Egyptian word for what we in the West would call “gods,” though the Egyptian understanding of the neteru was more abstract than the personages we think of as gods and goddesses; the neteru weren’t so much “divine people” as they were principles. In this view, the neteru all exist more or less in harmony with one another—except for Set, “the neter against the neteru,” who stands apart from all the rest—and thus apart from nature itself. This Setian “offishness” reflects the relationship above between the OU (which would correspond with the neteru whose wills govern the OU) and the SU (which would correspond with Set).

Putting all of the above together, we arrive at a conception of Set as the neter or “principle” of isolate intelligence or individual consciousness, among other things; we are able to stand apart from the natural universe and observe it—as well as ourselves—because Set, standing apart from the rest of the neteru, establishes the basic pattern of individual being and becoming; hence, the formula of “Xepera Xeper Xeperu,” or “I Have Come Into Being, and by the Process of my Coming Into Being, the Process of Coming Into Being is Established.”28

This entire system of thought can be basically summarized in Platonic terms, and Michael Aquino’s philosophy was deeply informed by both Plato and Pythagoras. In these terms, Set can be thought of as the “ideal Form” of self-consciousness. In fact, Setians have been described succinctly as “Neoplatonists who use an Egyptian metaphor.”29

The above review does not constitute an exhaustive detailing of every tradition that falls under the contemporary Left Hand Path umbrella. Rather, it serves to trace a path of usage of the term “Left Hand Path” through various traditions in a way that illustrates the strands of influence that converge to shape its contemporary usage. While it covers the most prominent and well-known influences, some traditions have been left out for the sake of brevity; most of these are unique syntheses that draw heavily from the influences already named, and can thus be considered “offshoots” of these main “trunks”. Other instances will be saved for later discussion, particularly in Chapter 2 on the vice of Hubris.

Defining the Contemporary Left Hand Path

The usage of the term “Left Hand Path” in the contexts above raises some important questions regarding cultural propriety: If, as was noted, the term was lifted from its culture of origin and used in such an inaccurate and culturally diluted way by the likes of Blavatsky and Crowley, why is it now used by an ever-growing contemporary subculture? Doesn’t the inaccuracy of such major links in the chain detract from the term’s legitimacy in any subsequent context that stems therefrom?

For reasons I’ll explain soon, I have intentionally kept this exploration of the Left Hand Path restricted to those who have used that specific term in their teachings; by contrast, the approach taken by Dr. Stephen Flowers in Lords of the Left-Hand Path was to establish a definition of the term, and then explore various religions and movements throughout history to which that definition would be applicable whether or not the term was ever adopted within the movement itself. Thus, his approach and mine are, on the surface, complete opposites in terms of orientation. However, I hope to illustrate how they are in fact complimentary to one another.

Simply put, it is highly doubtful that the book Lords of the Left-Hand Path would have been written if not for the chain of contexts I introduced in the previous section. While Dr. Flowers did explore each link in the above chain to a greater or lesser extent in the book, he didn’t necessarily make this clear. At this point in our exploration, it becomes worthwhile (and perhaps even necessary) to introduce the contrast between the emic perspective and the etic perspective.

The terms “emic” and “etic” originated in the field of linguistics, but were applied to that of anthropology in the 1950s and have since been adopted throughout the humanities.30 Each refers to a basic standpoint from which a human observer can describe human behavior.31 The etic perspective can be described as the objective, “outsider’s” perspective, established in an effort to facilitate a scientific approach to the study of culture. It allows for a generalized system of classification to be devised by the researcher in advance of a given study, which is useful for comparing and classifying behavioral data from different cultures across the world. Due to this classifying function, the etic perspective emphasizes similarities between cultures. Although this is not clearly stated in the book, Lords of the Left-Hand Path was written partially from the etic perspective in that Dr. Flowers devised a set of classifying criteria for the Left-Hand Path and then applied it to many different religions, movements, and thinkers from different times and places.

By contrast, the emic perspective is the subjective, “insider’s” viewpoint, or the way a single culture is experienced by a member of that culture. Unlike the etic perspective, the emic perspective emphasizes differences between each culture, firmly holding a given culture as unique. This viewpoint dispenses with any hint of the etic perspective, exploring a culture on its own terms in a wholly relativistic way.

Ever since these two terms were first coined, academic debate has raged regarding their usefulness. The etic perspective can be problematic: It can be somewhat arbitrary, glossing over distinctions that are important on an emic level, which can rapidly confuse the very matters they are attempting to clarify. According to Mostowlansky and Rota in the article “Emic and Etic” on Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, “an emic approach would call attention to the fact that two etically idential [sic] behaviours can in fact differ profoundly, depending on the meaning and purpose of the actors.” A perfect example of this has already been alluded to here: As I discussed above, the term “Left-Hand Path” as used by Blavatsky has a decidedly negative connotation. Nonetheless—although he carefully weighs the case for and against and fully acknowledges the ambiguity of this particular example—Dr. Flowers concludes that certain aspects of Blavatsky’s work and teachings “may be sufficient to consider her a ‘lady of the left-hand path’—even though she might not like the terminology.”32 As a former Theosophist myself, I can tell you that from the emic viewpoint of a Theosophist, his proposition would be regarded as nothing short of blasphemous.

Another problem that arises with relation to the etic perspective is that it is arguably impossible to fully separate any given etic classification from the inherent emic biases of the person establishing it; that is, a researcher’s own way of classifying things may seem objective to them, but the classification itself is likely to be influenced by their own cultural perspective. This is most certainly the case when it comes to Dr. Flowers, especially when one considers that at the time Lords of the Left-Hand Path was written (and in the time since), he was a member of Temple of Set—one of the very Left Hand Path schools analyzed in the book. To his credit, Dr. Flowers acknowledges as much in the Preface when he states that, “the purpose of this book is to elucidate the darkness and inform the reader from the inner perspective of the path itself.”33 A proper understanding of the etic and emic perspectives thus becomes an important key to fully understanding the book, which, despite the line quoted above, applies both perspectives without making explicit reference to either. He does speak as a practitioner of the Left Hand Path, but with regard to most of the particular traditions he covers in the book, he speaks as an outsider.

This is why I took the time to review the above “evolution” of the term “Left-Hand Path,” focusing solely on those who have made conscious use of the term. Some of the verbiage in Lords of the Left-Hand Path, especially near the beginning, can give the impression that the LHP is a path permeating all of history, a grand and sinister tradition in which its participants have knowingly taken part. The reality is that from a purely historical standpoint, this simply cannot be true. What Dr. Flowers does not directly spell out—although he leaves us all the clues we need to piece it together for ourselves—is that from the emic perspective of a Setian, the path itself transcends history.

All of this is important in coming to understand the nature of the definition Dr. Flowers uses to classify the Left Hand Path. In the very first citation in Chapter 1, where his definition is given, he notes that “a chief source for this discussion is Aquino, Black Magic in Theory and Practice,” indicating that his definition is based firmly on Michael Aquino’s ideas.34 As I have shown, Aquino himself drew upon an established history that can be traced from Indian tantra to its interpretation by Blavatsky, Crowley, and Grant, which was then essentially co-opted (historically speaking, at least) by Anton LaVey. As I stated above, it was Aquino’s belief that Anton LaVey was the anointed “deputy” on Earth of Satan, or Set, or “The Prince of Darkness,” and that this held true regardless of LaVey’s own understanding of the situation. In fact, it neither stopped nor began with LaVey. The Book of Coming Forth by Night—which Aquino maintained was infernally “inspired” by Set himself and was written as if in Set’s own words—specifically named Anton LaVey as his previous “Magus,” and further claimed that the being named HarWer, known by Aleister Crowley as “Horus,” was Set’s own “opposite self.”35 As the narrative goes, Set (as HarWer) first tapped Crowley to carry his message, but Crowley was unable to break through the guise of HarWer to commune fully with Set himself; through the work of Anton LaVey (whether he realized it or not), Set and HarWer were fused as one, at which point Set “anointed” Michael Aquino to carry on his legacy.36 What this implies is that, above and beyond any impact Crowley’s writings had made on Anton LaVey, there is a direct spiritual “lineage” linking Crowley, LaVey, and Aquino himself through Set’s influence.

Whether or not you, dear reader, take these beliefs to be true, one thing is certain: Michael Aquino did, and these three figures alone cover quite a bit of the ground established in the previous section about the evolution of the Left Hand Path. Even if his belief were in something unreal, we could thus safely conclude that the figures of Aleister Crowley and Anton LaVey stood out prominently in Michael Aquino’s SU or psyche and were thus important to him in connection with his understanding of the LHP. This means that at the very least, Aquino’s own understanding of the term was likely a synthesis of the various applications of the term up to that point, combined with his own studies and lastly, with his own “inspirations” via Set. Since Dr. Flowers showed that his own definition was largely synthesized in turn from Aquino’s understanding, we now have a fairly clear picture of the main influences that come together to form the definition Dr. Flowers used.

If you do take Aquino’s ideas regarding The Prince of Darkness and his “anointed deputies” at face value, you can also understand how such a perspective likely informed Dr. Flowers’ decision to confidently apply that definition of the LHP retroactively to various figures and movements regardless of their historical connections or lack thereof; after all, if you believe the Prince of Darkness became personally involved with Crowley, LaVey, and Aquino, it would be foolish to believe they were the only ones in all of human history. If the narrative contained in The Book of Coming Forth by Night is true and the Set entity is real, that entity has probably been very busy throughout history, “inspiring” others in like manner; its interest would in no way have begun with Aleister Crowley, nor should it be expected to end with Michael Aquino or the Temple of Set as a whole. Rather, based on an understanding of Setian cosmology and theology, Set has most likely been intimately involved with his “Elect” (Michael Aquino’s term for those capable of undergoing LHP initiation) since the very beginning, though under many different guises; perhaps he was perceived in Scandinavia as Odin, or in India as Shiva. Perhaps “he” reaches out to others still, as Lucifer—hell, as Hekate—or as a towering red dragon. Regardless of the specific mask worn by The Prince of Darkness, from the Setian viewpoint, the essence of the Left Hand Path is that of consciously realizing the potential to Xeper—or in other words, to become “Set-like.”

The Purpose of This Book

With all of the above so painstakingly laid out, it’s now time to discuss the purpose of this book and the method of its approach.

One purpose of this book is to stand up for the Left Hand Path, to protect the Black Flame, as it were. The question is: From what?

Sadly, I have to answer that by saying, “From itself.”

I’ll be going into greater depth about this in a later chapter, but I myself have some considerable roots in the world of Theosophy, mentioned above, where the Left Hand Path is a big no-no. As I expressed, in some Theosophical circles, the core values of service and selflessness are sometimes taken to such great extremes that there’s tremendous felt social pressure to show your peers that you’re a good Theosophist; if you’re being too self-centered, you feel the burn of embarrassment painting your cheeks. In discussion groups, people who are overly fascinated with psychic phenomena or the colorful visions of the astral world painted by clairvoyants are gently shunned and talked about behind their backs for being “less developed” and such. You don’t even have to be actively selfish, sometimes you feel like people are looking out the corners of their eyes at you because you’re not selfless enough, not going far enough out of your way to assist your fellow human beings. At a subcultural level, it’s toxic positivity and spiritual bypassing at best, but can veer into manipulation and control as well.

However, while I was working and speaking there, I found myself at variance with the above attitudes. I largely kept to myself, and while I can be a very compassionate person, I also did enough hard living at a young enough age that there are times when I’m practically numb to the kinds of things that seem to raise emotional responses in others. I have always been very focused on myself, it’s true, and we’ll discuss some of the detrimental aspects of this in Chapter One, but not every reason was bad: One major one was that I realized I have no direct control over the actions of anyone but myself, so I might as well focus on the things I do have control over—and even then, the self-control I did have left something to be desired.

Secondly: My indwelling nature was somewhat deceptive, because I had always felt a sense of meaning and purpose in my life that has to do with making a contribution to the world and to humanity. Once more, I also figured that the best way I could make the world a better place would be to make myself a better person. However, for whatever reason, I simply never felt like I fit in or could be myself at the Theosophical Society’s headquarters.

When I first began writing about the vices and virtues, those negative value judgments about the LHP were the thing I was “standing up” to; I felt a burning passion to articulate how the goals of the LHP were wholly compatible with living a so-called “spiritual life.”

Another threat to the Left Hand Path has historically been Christian conservatism: Many people are aware of the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s, when false allegations of Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) filled the headlines. It was a modern-day witch hunt with many victims, some of whom spent many years in prison. It was all started by a book called Michelle Remembers, written by Michelle Smith and Lawrence Pazder, M.D. According to the book’s claims, Pazder uncovered “repressed memories” from Michelle’s childhood of alleged Satanic rituals in her home, complete with women being impregnated just to give birth to babies who were later sacrificed. It’s notable that Pazder went on to marry Michelle, and the book has since been discredited; however, that bell cannot be unrung, and must instead sound itself out. It rings still, and there are parts of my country where I wouldn’t want to live while openly walking the LHP, but books like Lords of the Left-Hand Path went a long way toward cleansing the LHP of this particular reputation. When I began writing this series, I was less worried about this aspect of social opposition to the LHP.

There’s one notable name attached to the Left Hand Path that I left out of my exploration above for two main reasons:

The overview above details a specific “lineage” of Left Hand Path thought, and this man wasn’t strictly a part of it.

He’s problematic enough that he should be dealt with separately and delicately.

I refer, of course, to the infamous Julius Evola.

We will go into greater depth about him in Chapter Two, but for the purposes of this introduction, it’s enough to say that he was a philosopher (of sorts), political thinker, and occultist who lived between 1898 and 1974. The other important detail about him is that he had deeply fascist sympathies. Believe it or not, when it comes to the damage his ideas have done to the reputation of the Left Hand Path, that detail isn’t even the most critical one; the most critical detail is what his justification was: In a nutshell, it came down to, “Because I want to, and I can because I’m a European man.” It is for this reason that the chapter in which I’ll spend the most time on him will be the chapter about the vice of Hubris.

Evola is possibly best known for his work Ride The Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul, a book in which he lays out his critique of the modern world and establishes the myth of the “differentiated man” or the titular “aristocrat:” A sort of heroic, godlike human (he’s really just thinking of men—white men) who is supposedly of a completely different “spiritual race” from most human beings; a true god among men. He couches this myth in the cosmological framework of the Hindu Yuga Cycle, reckoning that we are living in the Kali Yuga. He tells us this is the last of the four stages of the cycle, the farthest away from spiritual perfection, the one most riddled with sin, misery and debauchery. In the Kali Yuga, the usual spiritual laws and rituals of “Tradition” are shirked. From these two elements, he forges an argument that in an age such as the Kali Yuga, there is nothing for this “differentiated man” but to “ride the tiger,” which is to say he should make himself like unto a god by completely dissolving all of his morals and doing as he pleases. While in Thelema, it is pointed out to all new initiates that “Do What Thou Wilt” does not mean “do what you want,” in Evola’s philosophy, that’s exactly the meaning of spiritual achievement. In particular, Evola advocates for a complete withdrawal from political and social life to the greatest extent possible for the “aristocrats of the soul” during this period, mainly because he holds participation to be fruitless.

It’s a wholly pessimistic worldview, characterizing the world as a vapid and barren wasteland and urging the “differentiated” to make the most of it by simply seizing what they can in order to get by and living in seclusion while the world burns. It targets a certain audience (occultists and other spiritual practitioners) who are often known for being prone to fantasy or escapism and puts these pernicious myths into language that presents them as factual. In addition to the fantasy-prone, the material is bound to attract the kind of person who would pick up a book filled with language about a “superior” type of human being and, naturally, think that its author is speaking to them. This is the worst kind of person you want to be telling, “The world is ruined and only getting worse, so you might as well grab what you can,” unless you want authoritarian rule—which, of course, Julius Evola did.

What’s the problem with this from the perspective of the present discussion?

It follows a well-known playbook that has been used to great effect by authoritarian movements elsewhere. To this day, the fact that the tactic remains so effective is one of the biggest problems of human nature that we face (assuming we want to build a world of prosperity—and why wouldn’t we?). It involves dredging up fear, resentment, and a feeling of danger or precarity while appealing to an artificially-constructed, mythic past as the one path to safety, comfort, and renewal. One of the reasons it’s so confounding that this works so well is how often the “mythic past” used as the lure is so patently false that it falls apart under about an ounce of critical thinking.

Having written other books on the topic of Left Hand Path tantra, as well as having established an esoteric group called the Ur Group to practice his unique brand of Hermeticism, Evola has a reputation as an authority on such topics. The problem is that he wasn’t one. To some degree, we can credit historical influences of the time for the state of affairs: Europeans were much more ignorant of other cultures, and it wasn’t as well understood back then that an Italian guy living in Rome, reading a few books and engaging in some practices, probably isn’t the best person from whom to learn about Hindu calendrical cycles and spiritual teachings. Ride the Tiger contains chapters filled with blatant misogyny and racism, and subtly hangs a gigantic justification for them on the idea that we’re living in an age of desolation anyway that will always pale in comparison to the Golden Age we’ve lost. There is no other justification made for why the reader should adopt Evola’s stark prejudices than, “There was a Golden Age when these were the rules,” with the unwritten suggestion that it was the bigoted rules that made that age so “Golden.” However—so the proposition goes—since the world has gone off those rails, it’s up to “the differentiated man” to preserve those traditions until “the Golden Age” returns.

The book is written in tiresome philosophical language that makes his ideas appear very sophisticated, but I can summarize the entire book in a single sentence:

“Once upon a time, the world was great because women knew their place and there was no jazz music, but since the uplifting of women and people of color is wrecking the planet, it is imperative that white, upper-class masculinity preserve the moral codes that excuse its oppressive behavior so that it can all be rolled back out once the burning stops.”

The irony is that Evola bases his vision of “the differentiated man” on an Heroic ideal, but what he’s basically saying is, “Now that all of the arbitrary rules upholding our hegemony are crumbling, we should withdraw from society entirely.” In other words, “We’re not getting our way anymore, so let’s turn tail and sulk.” This does not seem very “Heroic” to me, and it just looks ever worse and worse when I view it through the lenses of the 7 vices and 7 virtues of this book.

This is the reason I have treated Evola separately from the others: Because by the philosophical understanding of the contemporary Left Hand Path as laid out in this book, there’s almost nothing about Evola’s philosophy that aligns with it. There is one element that stands as an exception, and it’s the one I’ll be examining in Chapter Two.

This is a problem: I’m sitting here writing the introduction to a book about the Left Hand Path and saying that Julius Evola had almost nothing valuable to offer it; meanwhile, it is increasingly the case that the very label of “Left Hand Path” now almost always makes people suspicious because of how many occultists currently use that label while holding Ride the Tiger close to the heart of their ideology. This has had destructive consequences, not only for society as a whole, but for the Left Hand Path in particular. It’s not doing the LHP any favors—not even in the “adversity makes us stronger” sense.

There is a new “Satanic Panic” dawning, this one of a wholly different nature from the religiously-oriented one of the 1980s. It is different in two ways:

The ground for the uproar is now political rather than religious.

The news stories fomenting it are actually happening this time.

We can also almost certainly lay this at Julius Evola’s feet.

In 2021, a man named Danyal Hussein killed two women in a London park as his part of a demonic pact he had made in hopes of winning the lottery.37 The most direct outer influence on Danyal’s decision to do this was E.A. Koetting, a black magick “shock jock” who was removed from Facebook as a result of his teaching that becoming a true adept of the dark arts requires making the ultimate sacrifice of one’s entire relationship with ethics. Indirectly, this idea was popularized in occulture by Ride the Tiger. Koetting was subsequently banned from Facebook and YouTube, and had several of his books banned from Amazon for promotion of violence.

In 2023, U.S. soldier Ethan Melzer was sentenced for his involvement in a plot to coordinate an attack on his own military unit by jihadist forces.38 This was connected with his involvement in The Order of Nine Angles (O9A), a “Traditional Satanist” group that employs the same tactic as Evola of weaving a false myth of tradition from parts of other religions and philosophies so as to justify what they do. The particular conundrum posed by this group’s existence is that rather than weaving its myth from popular world religions, it has instead borrowed the familiar Aeonic framework introduced by Aleister Crowley and used this as a scaffolding to synthesize an esoteric formula that includes elements from all major branches of the wider esoteric subculture. This is interesting because normally, some of these different streams of esoteric thought have basic disagreements and largely stick to themselves, but in bringing all of these elements together, O9A has ensured that all sorts of different people seeking different kinds of esoteric knowledge are more likely to find their way to the Order.

It’s important to note that O9A is a special case due to its decentralized, cell-based organizational structure, meaning it is not a monolith. It’s also secretive enough that much about its origins comes to speculation at best by outsiders. However, its founder, who goes by the name “Anton Long,” is widely thought to be a neo-Nazi named David Myatt.39 Its ideology isn’t explicitly tied to any one particular political perspective, though the central myth and goal of the group is to bring about a new global order, through means indicated to be militaristic, based on its esoteric principles. It, too, enshrines various practices that emulate the shedding of morals and ethics advocated by Evola, which is almost certainly what led to Melzer’s actions, along with a handful of others. The resulting media coverage makes this one of the Left Hand Path’s greatest liabilities.

What do I mean when I say this?

This is an extremely delicate matter, because in one sense, the stepping outside of the normal social order is the very definition of the Left Hand Path, and this is the part where I may shock my readers and say that in principle, I don’t disagree with the assertion that there is value in pursuing this kind of personal freedom. I began this section focusing on Julius Evola, but this really goes back to Nietzsche with his thesis that the Overman should go “beyond good and evil.” There is overlap here with the spiritual themes raised above, in that the process of Initiation eventually reaches just such a stage. It’s not the mere transcendence of morality that is the problem; while not every person is mature enough to wield that kind of power, Left Hand Path imperatives obligate the Path’s initiates and adepts to align their actions with creating a world where this pursuit is supported. This is because there’s no good reason that a person capable of wielding this power responsibly should not be allowed to do so.

This book is founded on the recognition of something of a paradox regarding the Left Hand Path: By its very definition, it is centered upon the self and its individual freedom and empowerment. On the surface, this can sound positively anti-social. It especially sounds that way to those unconscious parts of ourselves that are still wrapped up in the same herd mentality that the Left Hand Path initiate seeks to escape.

However, let’s look again at Anton Szandor LaVey. I myself am not a big fan of him as a person. He made quite a few decisions throughout his life that I find despicable based on the values I choose to live by. There’s a lot of hypermasculine “strongman” resonance between the thought of LaVey and that of Evola that has certainly led to some social ill. LaVey was a touch wrathful, too.

However, what hid underneath that anger?

Look where it was directed, and why: Against the religious and political institutions that oppress people. Yes, his methods were highly flawed and questionable (at least from where we’re sitting now) and no, I don’t think I would like to be his friend, but I can say that his heart was in the right place.

He would not have formed a church out of his convictions if he were not, in some way, trying to help others live their best lives, to be happy and free. Like it or not, Anton LaVey was working to build a better world, only wishing to tear down the things that stand in our way.

I can also say that there’s more to an assessment of the worth of a person’s ideas than their own content, and that because of this, I would still say the net result of Anton LaVey’s work has been more beneficial to human freedom, overall, than it has been detrimental.

Occasionally, vulnerable, disturbed and unwell people pick up the darkest literature and follow it to its very darkest places, often even distorting the message so much that they take it to a place that is darker still than was intended by its author. This happens, and when we speak or write on this, we should keep this in mind. But how many people who read The Satanic Bible do you think just blindly followed every word LaVey wrote? Do you not suppose that a person who thinks independently enough to even pick up such a socially controversial book might also be apt to read it critically?

Amazingly, I still have a lot of faith in people, and that’s really one of my own major points of connection with the Left Hand Path. I believe in people, I love people, and I want to see all of us be the best version of ourselves. I believe the Left Hand Path is the place to do it because the Left Hand Path stands in opposition to oppression…

...in principle.

It’s the praxis that leaves a lot to be desired.

Not everyone is like me. Not everyone is drawn to the Left Hand Path for positive reasons. Not everyone is here to build. Some are here exclusively to destroy. There will always be people who are drawn to the path because they see in it a permission slip to let the worst parts of themselves run wild.

It’s people who do that kind of thing that the Left Hand Path stands against, so these people are clowns. Who were the church fathers Anton LaVey condemned? They were self-serving, ruthless power brokers.

The world we are working to build is a work in progress, and the social, religious, political and institutional forces that must be deposed in order to do so are very deeply entrenched. As such, I have always felt that the earlier stages of this project were always bound to be messy. The way had to be cleared. It had to be explosive in order to knock down some very sturdy walls.

Now, however, is the time to get more surgical. Now we are in the stage of subtlety and nuance. We recognize more explicitly than ever that evolution for us now requires thinking of where we can set limits that will better support our growth. After all, the Left Hand Path is often regarded as the path of Saturn, and it doesn’t get much more Saturnian than setting limits to support our thriving. Part of self-mastery is the mastery of one’s desires; mature Left Hand Path initiates know they need to pick and choose which ones to chase. We also know when it’s better to endure some hardship or loss for the sake of our long-term development.

Without further ado, I present my perspectives on the 7 vices and 7 virtues of Left Hand Path initiation, which I feel in my heart of hearts can guide us home to the world we all know we want to live in.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 24.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 26.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 26.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 234.

“Ma-Mam - Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary.”

“La-Li - Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary.”

Crowley, Magick, 480.

Crowley, Magick, 295.

Crowley, The Confessions of Aleister Crowley, 399.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 259.

Grant, The Images and Oracles of Austin Osman Spare, 7.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 45.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 23.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 52.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 304.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 55.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 40.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 44-45.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 25.

LaVey, The Satanic Bible, 81.

Aquino et al., The Satanic Bible, 45.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 323.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume I, 18.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume I, 22.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume I, 144.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume I, 147.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume I, 33.

“Set and the DNA.”

Aleister Crowley & The Temple of Set with Don Webb.

Mostowlansky and Rota, “Emic and Etic.”

Mostowlansky and Rota, “Emic and Etic.”

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 241.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, xi.

Flowers, Lords of the Left-Hand Path, 446.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume II, 34-35.

Aquino, The Temple of Set Volume II, 35-36.

Lamoureux, Mack. “Facebook Just Booted a Satanist Accused of Inspiring a Man to Kill 2 Women.” VICE (blog), October 21, 2021. https://www.vice.com/en/article/facebook-just-booted-a-satanist-accused-of-inspiring-a-man-to-kill-two-women/.

News, A. B. C. “US Soldier Ethan Melzer, Described as ‘the Enemy within,’ Sentenced for Jihadist Plot.” ABC News. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/US/us-soldier-ethan-melzer-enemy-sentenced-jihadist-plot/story?id=97616439.

Inform. “‘Cultic’ Religious Groups: Order of Nine Angles.” GNET (blog), August 3, 2023. https://gnet-research.org/2023/08/03/cultic-religious-groups-order-of-nine-angles/.

Aleister Crowley & The Temple of Set with Don Webb, 2022.

.

Aquino, Michael. The Temple of Set Volume I. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

———. The Temple of Set Volume II. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014.

Aquino, Michael A., Stanton Z. LaVey, Diane LaVey, and Satan. The Satanic Bible: 50th Anniversary ReVision. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018.

Crowley, Aleister. Magick. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1973.

———. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. Edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant. Reprint edition. London: Penguin, 1989.

Flowers, Stephen E. Lords of the Left-Hand Path: Forbidden Practices and Spiritual Heresies. Reprint ed. Rochester: Inner Traditions, 2012.

Grant, Kenneth. The Images and Oracles of Austin Osman Spare. London: Muller, 1975.

Inform. “‘Cultic’ Religious Groups: Order of Nine Angles.” GNET (blog), August 3, 2023. https://gnet-research.org/2023/08/03/cultic-religious-groups-order-of-nine-angles/.

“La-Li - Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary.” Accessed August 15, 2024. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/etgloss/la-li.htm.

Lamoureux, Mack. “Facebook Just Booted a Satanist Accused of Inspiring a Man to Kill 2 Women.” VICE (blog), October 21, 2021. https://www.vice.com/en/article/facebook-just-booted-a-satanist-accused-of-inspiring-a-man-to-kill-two-women/.

LaVey, Anton Szandor. The Satanic Bible. New York: Avon, 1969.

“Ma-Mam - Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary.” Accessed August 15, 2024. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/etgloss/ma-mam.htm.

Mostowlansky, Till, and Andrea Rota. “Emic and Etic.” Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, November 29, 2020. https://www.anthroencyclopedia.com/entry/emic-and-etic.

News, A. B. C. “US Soldier Ethan Melzer, Described as ‘the Enemy within,’ Sentenced for Jihadist Plot.” ABC News. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/US/us-soldier-ethan-melzer-enemy-sentenced-jihadist-plot/story?id=97616439.

“Set and the DNA.” Accessed August 21, 2024. http://www.joanannlansberry.com/journal/pathmark/set-dna.html.