3. Now let it first be understood that I am a god of War and of Vengeance. I shall deal hardly with them.

4. Choose ye an island!

5. Fortify it!

6. Dung it about with enginery of war!

7. I will give you a war-engine.

8. With it ye shall smite the peoples and none shall stand before you.

Liber AL vel Legis

III:3-8

The above lines are among some of the most stirring in Aleister Crowley’s Liber AL vel Legis, or The Book of the Law. The Book of the Law is considered to be the main sacred text associated with Thelema, the esoteric system and teaching bequeathed to humanity by Crowley. Among Thelemites, it is considered the one aof the few non-negotiable pieces of literature. In short, this book is said to be the “playbook” for the entire Aeon of Horus, inaugurated by Crowley and his writing of the text.

Although he published two commentaries attempting to interpret the text, the common tradition is that Thelemites consider the interpretation of the text to be a largely personal matter. When my own copy of the Book was given to me after my Minerval Initiation in the Ordo Templi Orientis, I was told that no one has the right to interpret it for me and that independent study of the Book would be an important part of my Thelemic journey.

I have my ideas about why this is, and they relate to aspects of the Word of Hermekate—most particularly, to the concept of The Song. In short, while Crowley may have his own interpretations which, as the person who wrote the book, should probably be given priority—and while it is certain that various passages of the Book are references to ideas and symbols employed elsewhere in his large body of work, likely included for students to diligently seek the key to their meaning—I theorize that many of the Book’s odd, vague passages are intended to mean very different things to various different people, and this is especially true if you choose to believe in the spiritual origins of the text (as opposed to holding the view, as Israel Regardie must have, that the book was nothing more than a “spilling” of Crowley’s personal unconscious mind onto its pages): In a spiritual view, it is possible that the entity or entities connected with the writing of the Book are able to see the universe from such an unimaginably lofty, “multidimensional” perspective that it’s certainly possible that some passages may have always been intended to hold very particular, idiosyncratic meanings, even for specific individuals who would one day read it, and that all of those particular meanings might be valid insofar as they resonate with the person who forms them—even if some of them actually seem to conflict with one another.

Those who have read Song of Twilight, wherein I describe in detail how Songs unfold from an individual perspective, and how they involve input from many different people, who may or may not have intended things the way I interpreted them, will perhaps see what I mean by this. The basic underlying theory involves a deep understanding of synchronicity and suggests that there is an underlying harmony in the universe which serves to reconcile the individual, subjective perspectives of everyone, even if it seems like we are all on completely different wavelengths in terms our views and understanding of the world. One major purpose of this post is to explore how that perspective, via the Word of Hermekate, serves as a way of overcoming (or taking part in) the “spiritual war” I’ve been referring to throughout many recent posts. A secondary purpose is to more fully articulate just what this “war” is.

In keeping with the above theory of how the Word of Hermekate relates to The Book of the Law, I have three books, from three separate authors, that each offer commentaries on The Book of the Law—and consequently, I have ready-to-hand three very different interpretations of the above verses.

According to the commentary by Michael Aquino, found in his The Temple of Set Vol. II—my least favorite commentary by far—the passages might refer to World War II, as well as to the invention of the atomic bomb which ended the war. It’s kind of a superficial and uninspired take, in my sincere opinion. Those interested in reading these commentaries might do better to save money by simply purchasing Don Webb’s Overthrowing the Old Gods: Aleister Crowley and The Book of the Law, as it contains not only his own, much deeper and more insightful commentary, but also includes a reprint of Aquino’s commentary for comparison. Webb addresses precisely the same set of verses I have quoted above thusly:

In verses III-3 to III-8, the martial nature of Ro-Hoor-Khuit is made clear. The war gods on the Stele of Revealing—Montu, Khonsu, and Horus Behdety—are his companions. The first job of the new and renewed self is to avenge his father. Who is the enemy? Is it Set, the daemonic initiator? No, it is the perceived notions of humans. All of the aspects of culture and society must be fought on two planes: inside your head, where the radical perspectivism of the adept will lead one to self-discovered truth, and on an outer level.

p. 119

I stopped the quote there because these were the comments most relevant to a general audience; as he continues, he goes on to interpret the verses in Crowley’s own specific case, as referring to the estate he established as a personal sanctuary to wage his portion of the “war” that is taking shape—the same war to which I have been referring of late, and the one inaugurated by Crowley’s work and utterance of the Word of Thelema.

Lastly, Edward Pandemonium offers his own insights in The Gospel of Pandemonium, which are quite relevant to the current form this war is now taking:

While conventional warfare—or at least the use of its weaponry—is still very much a thing, I am going to say that the nature of war has changed again following the conceptual evolution that has happened through the Age of Satan and Aeon of Set, as well as simply a century of world change in general. This evolution in the character of our “god of War” is explained in the Book of Coming Forth by Night by the statement that the Aeon of Horus was a period of purification to create space for true creation under Set (see the comment to verse 35 for much more detail on this relationship). The new form of Total War that I advocate is prosecuted through BUILDING. Its destruction is creative, its disruption is transcendence. I came to realize and embrace this conception of war in stages. My original interest, relevant to the previous chapters of this Book, was in determining how one might become and reign as an actual King in a world and age where the traditional means of becoming and reigning as a King have been made somewhat obsolete and rather difficult to put into practice. I was inspired by the (albeit Right-Hand Path) use of “think tanks” and strategic philanthropy by Charles, Prince of Wales, and the Aga Khan. While I was experimenting with my own nonprofit organization, I learned about the book Unrestricted Warfare written by two Chinese military officers, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui. This book expands from the use of “think tanks” and propaganda to the use of international law, economics and the exploitation of networks. Later, Michael Aquino—a career military officer and the Magus of the Aeon of Set—released his book-length explanation of MindWar, which provides a useful structure.

From these elements, the new type of “war” can be drawn out and put into practice on any scale, compounding gains to build up force and leverage, lessening the asymmetry between actants.

pp. 75-76

My thoughts in this chapter of Inner Tarot Revolution dovetail with the subjects opened in the previous two posts in the series, Chapter 33 and Chapter 34. First, I wanted to add a couple of comments to the perspectives I aired in Chapter 34: As ever, I find myself second-guessing much of what I wrote.

For one, it bears mentioning that Jason Louv runs a whole-ass magic(k)al school, and that the video I critiqued in my most recent post is likely meant largely for his students there, and he was likely keeping in mind that many of his students are relatively new to all of this esoteric stuff. As such, he was likely presenting a simplified view of things meant mainly to help develop the understanding of his students (and those on a similar level) without unnecessarily confusing or misleading them. He’s over at his channel trying to keep things simple and tailored for an audience that still has a lot to learn, and I’m over here splitting hairs and making a federal case about “nuance.” It’s a misstep that I feel like I make a lot. There’s a lot at stake, and more than likely, the people capable of handling the kind of “nuance” I addressed in the post probably don’t need me to explain it to them, either. So, in a more critical vein regarding my own work, sometimes I think I’m too sloppy in my approach and tend mainly to make matters worse. Sometimes I feel like I’m wasting my time by writing what I do, because I wonder what actual good it’s doing anyone to share these thoughts.

I admire what people like Jason Louv do, and I would not be able to do it. The same goes for everyone else I have criticized in my writings, from Aleister Crowley himself to Anton LaVey, Michael Aquino, and even James Fitzsimmons. I didn’t learn about magic(k) in a very structured way at all. I stumbled through book after book by myself, with input from Rose and Ilyas, who may just have been figments of my imagination anyway. There is very little I can offer to the kind of people who are in need of something like Jason Louv’s school, or anyone’s school. And maybe I’m just making a big mess over here. I’m not sure who I’m really benefiting through these writings. I only rebooted Dark Twins at all because I started getting the impression that someone I know happened to believe in what I had been doing, and I got some confirmation of this when people threw a “Like” onto my Facebook post announcing the reboot. Maybe it’s worth trusting them, but I very often feel like I know much less about what I’m doing than I think.

I really can’t wait until this series is done; I’m only continuing it because I’m so close to the end anyway. It’s all just to dignify the effort I’ve already spent on it.

Anyhow, since my last post, I’ve made it about 80% of the way through the book Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul, and while I am going to finish it, I also have serious doubts that I need to finish it in order to see whatever it was I needed to see in the book. It’s another reason I’ve been second-guessing my latest writings, because I spent a lot of energy making a case against canceling literature like it, and yet now that I’ve read most of it, I gotta say…I’m not that impressed. After all this build-up over the last few years, the end result feels pretty anticlimactic.

That being said, while I don’t necessarily disagree with everything Evola expresses in the book, I can see major problems with how it’s all presented; this book was not my initial exposure to many of the concepts Evola treats, and I think that’s a good thing. Talk about misleading newer students: I can now see why many people regard the text as potentially dangerous. I think it’s likely that I only managed to sidestep many of the mental “traps” laid in the book because these ideas aren’t all that new to me. However, I can fully recognize the ways in which a much younger version of me would have been blown away by the book, and led thereby down certain pathways that the current version of me would never find fruitful.

In that sense, I am glad I’m reading the book because it gives me a better sense of what one who upholds values like personal freedom and the worth of individual human beings is up against in doing their part to shape the kind of world they would enjoy living in. In other words, it has done a lot to develop my understanding of the theater of the “spiritual war” I’ve been writing so much about. In a chilling mirror of the comments I made above about my own writing: This is not the kind of book I would ever recommend to beginners of spiritual and esoteric studies, unless I were invested in indoctrinating them into certain highly prejudicial viewpoints.

As far as I can tell, the title itself is a lie of sorts: As “A Survival Manual For The Aristocrats of the Soul,” one would assume it’s a book meant to aid the kind of person described by said title, and unfortunately, I am sure that’s exactly what Evola would have liked his readers to believe. However, the way the book is structured suggests to me, instead, that the book is meant to cultivate and develop “Aristocrats of the Soul” as Evola defines the term. The way he works toward this is both subtle and cunning.

The first couple of chapters of the book form its main premise, and everything that comes after is built on this foundation: Evola describes a “type of man,” which he terms “Traditional man” and describes as a type of man from “a different world,” which he implies via a vague introduction of the “Doctrine of the Cycles,” or the model of time known in Hinduism as “The Yuga Cycle,” is a person attuned to a bygone age of spiritual tradition, the “Satya Yuga” or “Golden Age.” I described this cycle in Chapter 33, and the details I provided there should suggest everything a person needs to know in order to immediately suspect Evola’s motives in making this connection between the Yuga Cycle and the “type of man” around which this book revolves:

Given the time frames described by the model of the Yuga Cycles, there is no way this model is describing something objectively real. According to the Yuga Cycle, this “Golden Age” to which Evola refers began in the year 3,891,102 BCE and ended in the year 2,163,102 BCE (although Evola does not tell you this, instead referring to the “doctrine” in only the vaguest possible terms necessary to make the idea appealing). Based on everything we know from the fields of anthropology and biology, humans as we know them didn’t even exist at that point. The Satya Yuga overlaps with the age of Homo habilis, the first species of the genus Homo. It’s impossible to know everything about the intelligence of such creatures, but we know their brains were no bigger than that of a chimpanzee and that Homo habilis had much more in common with actual apes than with what we now recognize as human beings. As such, there is no way they were living in some kind of “golden spiritual civilization” characterized, as Evola suggests, by its centering of “higher spiritual principles” that, as far as present science can tell, such creatures would have been completely incapable of understanding in the same way we do.

In other words, the Yuga Cycle is useful only as a myth—and as such, this concept of “Traditional man” upon which Evola builds this entire book is also a myth. This doesn’t mean the concept is entirely worthless; it’s worth quite a lot on a mythic level, but of course it only fulfills the best potentials of the mythic function if we actually know it’s a myth. Evola, however, presents this concept essentially as factual.

Evola’s description of this “Traditional man” is fairly vague, but nonetheless likely to resonate with many of his readers: He really doesn’t go much farther than to say those who belong to this type feel like strangers and outcasts in our modern world, and largely because they adhere to higher spiritual ideals that are by and large rejected by said world. The reason it’s so sneaky for Evola to tie these factors in with the idea of a “type of man” who “belongs to a lost age” is because truthfully, the symptoms he’s describing here are no more or less than a nagging sense of cultural alienation that was much more sensibly described by Karl Marx, which is indeed a result of many modern influences, though Marx describes these influences in economic rather than mythic terms; but of course, Evola expresses great disdain for Marxism in his quest to instead communicate this concept on the mythic level—a level which he proceeds to use to cleverly manipulate his readers as the book proceeds. This initial setup is meant as a “hook” for certain readers, compelling them to identify themselves (probably via flattery owing to the characterization of this “type” as “elite”) with “Traditional man.” From here, Evola goes on to exhaustively critique various aspects of modernity, chapter-by-chapter, all the while reminding the reader of the myth of “Traditional man” and describing how said type supposedly holds similar views to Evola. The thing I couldn’t help but notice was that the entire book is predicated on the assumption that the reader will buy into the myth of “Traditional man” from the very beginning, identify with it from the outset, and go on to look to Evola for “answers” as to how “Traditional man” should see the world. In reality, the whole thing is arbitrary. This “type of man” exists only in Evola’s own imagination and, insofar as he is able to convince his readers to continue identifying with this “Type,” he is subtly telling the reader what they “should” think and feel if they consider themselves to belong to said “type. Of course, one may feel rather compelled to do so because Evola establishes this “type” as being superior to most people—a quality many in his target audience would find desirable.

Along the way, Evola makes many points that are resonant and with which many readers of such a book are likely to agree—but he also works very hard to sell reasons for it all that don’t follow necessarily from the initial premises of one’s very real sense of alienation in the modern world. There’s a definite, ongoing bait-and-switch being executed here.

In short, you don’t need to fall into some preconceived “type” as described by Evola in order to agree with many of the basic sentiments he voices throughout the book. Far from describing some special “type” of person, Evola is largely appealing to feelings and experiences that almost everyone can likely relate to on some level, at least from time to time…but in so doing, he wants you to believe this puts you into the special class which he goes on to describe and define, and of course there comes with that the implication that you should behave in certain ways or hold certain views and values which he eagerly offers up to you.

He’s not just “describing” this “type” in so doing; he’s manufacturing it, hoping to shape and mold the reader into that type by setting it up as an ideal to follow, baldly assuming the reader will be impressed by his erudite and often highly academic presentation of an array of “facts” that don’t necessarily all hang together as a matter of course.

It only works insofar as his readers willingly buy into the narrative and fall for his many arbitrary leaps in logic; and, to read the positive reviews of his book, it seems many people just eat this up—again, because it allows them to hold a very flattering and self-gratifying view of themselves.

Of course, it just so happens that the “type” of mythic person Evola is conjuring up here is one that upholds a classically patriarchal, highly Eurocentric, definitely racist (he spends an entire chapter very specifically bemoaning the “bad influence” of Jazz music) and classist status quo. Probably the greatest irony of all is, again, that he actually makes some very valid points along the way addressing some of the potential pitfalls of a modern, materialistic perspective to which one of his seemingly favorite words, “dissolution,” is eminently applicable—just not necessarily for the reasons he suggests. He was no fool and the work is intellectually dense—I admit there are entire chapters that go right over my head for my own simple lack of familiarity with some of the subjects he treats that are of a highly technical academic nature—which just means that in order to be fooled by the central conceits of the book, one must indeed be pretty intelligent and well-educated. The end result is that there are entire legions of smug, thoroughly self-satisfied, though undeniably intelligent suckers out there who buy into this myth hook, line, and sinker. A lot of older, well-educated white men fall for it immediately. It’s…pretty ironic, really.

But as most people who value the spiritual dimension of life understand all too well, intelligence isn’t everything. There’s such a thing as being too clever for one’s own good.

At any rate, while the context Evola creates around it all is inherently arbitrary and very intentionally meant to serve a specific set of ideological ends, it is just as I said in Chapter 34: The reason it all works so well is because Evola does use some very deep, very real concerns as selling points. He addresses some rather universal points of modern despair, but repackages them as the unique concerns of his mythical “Traditional man”—concerns which are reflected well in this Chapter’s Sun and Shadow Cards. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain, of course.

So let’s do cards.

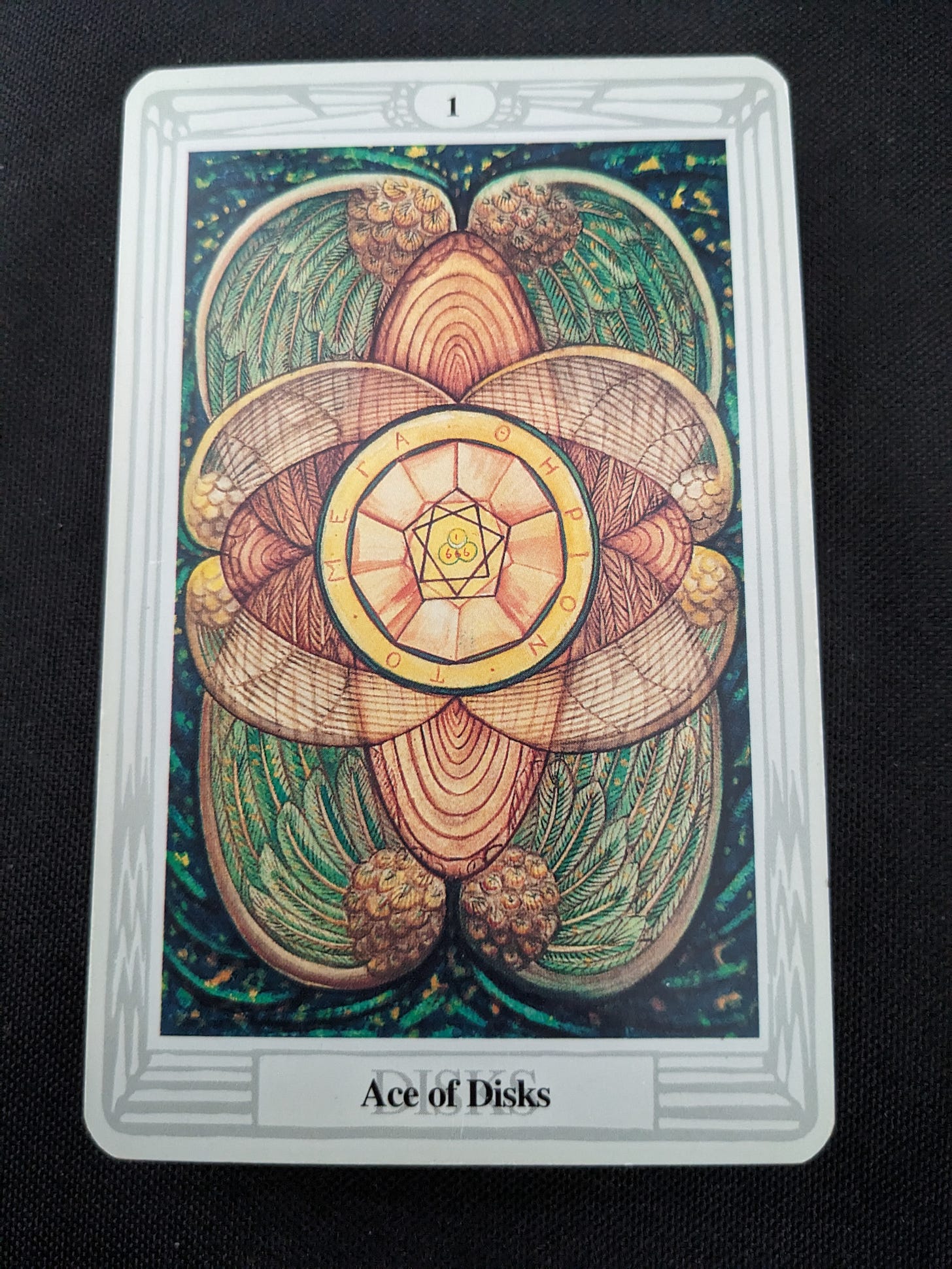

Top/Sun Card

The true nature of the “spiritual war” is somewhat complicated and the various “sides” in the war are multifaceted, but there are nonetheless a number of ways in which it can be described more simply and in terms of dualistic opposition; one of the more appropriate of those is to describe the war as being waged between the forces of spirit and matter. This description works in the sense that much of the ideological conflict in the world today is between people who champion one perspective over the other—not because the spiritual and material aspects of the world are themselves at war, but because different camps of human beings believe one is more important than the other.

Of course, different “combatants” in this war will have different opinions, but my own perspective is that the optimal end of this war would be a peace treaty.

Since Aces represent the very roots of their respective elements, The Ace of Disks—as the root of earth, the element of materiality—is the perfect emblem for the central battleground: The material world.

Historically speaking, one of the main reasons religion has held so much sway over the hearts and minds of humanity is simply because of how relatively little we have understood about the material world. Although it’s nowhere near being the entire story to quite the same degree that atheists/philosophical physicalists like to suggest it is, there is truth in the idea that myth and religiosity were once the explanatory “placeholder” for why things are the way they are, or how the world works. As our understanding of the material world has grown, our reliance on religion as the organizing principle in our lives has receded, and this is so true that in the infancy of science, scientists were hunted down and rooted out as heretics due to the threat their inquiry posed to the authority of the Church. The fear that our more deeply understanding the physical universe would “dethrone” God has always run deep, with the apparent supposition being that if God were to lose his place in the world, all hell would break loose.

This is the central anxiety that runs through Ride The Tiger; as intelligent as Julius Evola seems to have been, he couldn’t shake it. While I myself am much less reliant on spirit as an explanatory and semantic framework than he was, even I understand and relate to the anxiety about it. If anything, there are more numerous reasons to believe today that this anxiety is well-founded than there were while Evola was still alive.

The essential claim made by theists from the beginning of this already centuries-old conflict in worldviews is that without a spiritual or religious component of life—without some higher principle for humans to follow—there’s no foundation for morality to rest upon, and that we will ultimately lose our way.

The counterpoint made by atheists is that this is untrue, and that there are plenty of valid ethical frameworks to follow which do not rely at all on the concept of God or a spiritual world to stand up.

In principle, I would have to agree that atheists are right to assert that. Individually, there are many examples of people who prove it to be true via their actions and the way they live their lives.

Collectively, I think the jury is still out, and that those atheists who maintain a solid ethical compass that doesn’t include a spiritual worldview are a much rarer kind of person than they themselves would acknowledge—that they may represent the best of what is possible, but do not represent the human norm. And why would I say this?

Just look at the world we have created. Environmentally, we are wreaking complete havoc on it, and this possibility has mainly been opened up to us with the advent of a modern, materialistic worldview and its many consequences, including industrialization and the environmental devastation wrought by the endless pursuit of monetary profit enabled thereby. Yes, it is possible to maintain a high ethical standard without God, but it’s not necessary to do so, and I would argue that most people don’t live up to that standard. Those who do so are firmly the exception to the rule. It seems much more commonly the case that materialism is leveraged mechanically by people seeking to consolidate worldly power, to justify what they do by a simple negation of principle itself, effected by shoving God out of the way with no concern for finding something to replace his once central role in shaping common morality.

Of course, the argument from atheism would be that the only thing that has really changed, in that regard, is a shift in justification; that in the past, the same people simply used the concept of God to justify greed and cruelty from the opposite angle to that of materialism…and that is true. I wouldn’t argue otherwise.

All I’m going to say is this:

If humanity by and large had any sense of the material world as being “sacred,” we would not be treating it the way we do.

As I have said repeatedly: God is clearly not the answer. Religion can be, has been, and still is readily abused in manipulative and selfish ways; but shit-canning the sacred entirely is also not working out well for us. One of the more lucid sections of Ride The Tiger is Chapter 19: “The Procedures of Science.” In it, Evola doesn’t so much critique science itself as he does “scientism,” or the hubris that science can ever wholly replace religion as a framework for meaning. He rightly points out that, in fact, when science is properly understood, no one should ever expect it to do so. Science is meant to explain the “how” and the “what,” never the “why.” In my opinion, even greater than what we now identify as the folly of religion (as humankind once understood it) is the folly inherent in dismissing it entirely—in supposing that, since science indeed gives us a magnificent and ever-growing comprehension of the “what” and the “how”—that we no longer even need a “why.” The conceit of atheism, and the only reason I don’t personally embrace it, is that many people seem to have slotted science into the place religion once occupied, and to do so is actually to fundamentally misunderstand what science is meant to do for humanity.

It may be true in individual cases that many people do not feel the need for a “why,” but this does not really hold true for humanity writ large. Humanity writ large is and will continue to be a creature of narrative, and the error of “scientism” is that of throwing the baby out with the bathwater and expecting the merely utilitarian explanatory power of science to sufficiently nourish humanity’s inner need for narrative and meaning. This is a fundamental category error, and it’s just as wrong as thinking dogmatic religion was working out well.

Just because many individual atheists say they are perfectly happy without a “why” does not mean it will suit us all on a collective level; and many contemporary people, meanwhile, say they don’t need God as a “why,” but instead find their “why” in their familial relationships, in their chosen profession, in art, etc. This is wonderful, although I would point out that many such people are also still unable to fend off a deeper dissatisfaction with life, a nagging sense of depression that may have more to do with a lack of something fulfilling to place into the “spirituality” slot than they may realize (after all, having a contemporary, modern understanding of the world is not the same as having a deep sense of self-awareness). Lastly, it’s quite likely many people do have something else fulfilling, such as philosophy, with which to fill that void—but that, by personal preference, they don’t describe it as “spiritual” even though someone else who openly identifies as “spiritual” might do so; in other words, there are likely many cases in which one’s claim to being “non-spiritual” is merely a matter of semantics—simple wordplay.

Honestly, where I see all of this headed in the end is a situation in which the age of religion served as “thesis,” whereas the age of reason serves as “antithesis,” but that in the end, humanity will fare best once we widely agree on a synthesis of the two that can serve to balance our relationship between the outer, material world and the inner, subjective understanding of life that, indeed, makes us human. The main problem is that, at present, we are all out of sync: Many people have yet to accompany the modern world from the thesis to the antithesis which, in terms of popular acceptance, is still in the relative minority; as such, it only stands to reason that the number of people open to the synthesis in this scenario are even fewer still.

We have a long way to go, but that seems to be what we need to ultimately aim for, because absent any kind of inner or “higher” framework for relating to the world around us, we do largely seem to grow restless and unhappy, and we start to treat the world, and each other, like shit.

One of the reasons I sometimes question what I do, including my ideas surrounding the Word of Hermekate, is because, properly understood, the Word of Thelema went a very long way in establishing the necessary foundations for moving humanity from the thesis and antithesis in this scenario and into the synthesis. It’s a pretty deep philosophy and notwithstanding some of his character flaws, Crowley was also clearly a genius.

The only problem is that, having gotten caught in some of his own rather “Osirian” trappings, Aleister Crowley didn’t quite go far enough, necessitating the Word of Xeper and the Aeon of Set to carry some of his ideas all the way through to their most drastic conclusions that more deeply honor the unique subjectivity of everyone (in other words, the more elementary core concepts of Thelema are fantastic, and yet Crowley managed nonetheless to build his own particular “religion” around it all instead of remaining loyal to the purer, more direct interpretation of his own credo: “Do What Thou Wilt Shall Be The Whole of the Law.” Instead, the implication he leaves us with seems to have been, “Do What Thou Wilt—But Do It Like This, Please.”)

Given all of the above considerations, it’s pretty interesting that Crowley essentially turned the Ace of Disks in his Thoth tarot into one great big tribute to himself and his peculiar ideas. Basically the entire chapter on this card in Lon Milo DuQuette’s Understanding Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot is one long explanation of all of the ways in which Crowley used this card as his personal “signature:”

A tarot tradition dating back to sixteenth-century Italy (where decks of cards were stamped and taxed by local authorities) dictates that the creator of the deck place his or her mark or signature on the Two or the Ace of Disks. Crowley was obviously aware of this tradition, and I think we can be confident that he supervised its execution very carefully. The Ace of Disks is nothing less than Crowley’s own magical signature. His motto, ΤΟ ΜΕΓΑ ΘΗΡΙΟΝ To Mega Therion, Greek for the Great Beast, is displayed on the perimeter of the disk, and his personal seal is placed in the very center of it all.

p. 169

For better or for worse, “The Death of God” addressed at length by Friedrich Nietzsche and taken up by Evola played the much-needed role of freeing humankind from the tyranny of dogmatic religion, but simultaneously “cursed” us with the responsibility of finding a way to provide for ourselves that which we once thought to be the gift of God:

The meaning of life itself.

From this set of circumstances was ultimately born the philosophy of postmodernism—a double-edged sword indeed.

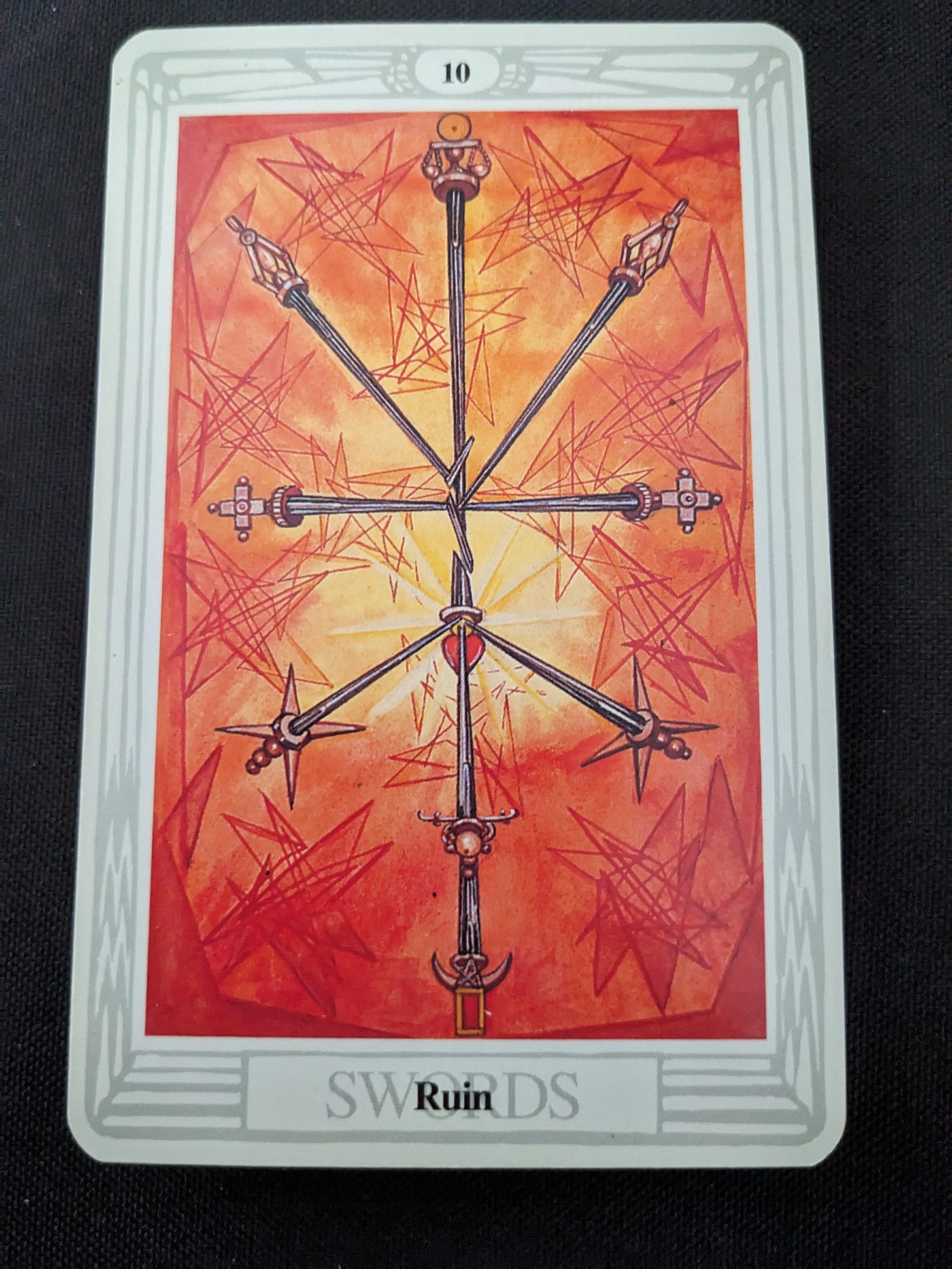

Shadow Card

It figures this card would show up now. Well, I had to deal with it eventually. Might as well get it over with.

When I first began writing the blog Gogo’s World of Ruin, which formed the basis of what is now the World of Ruin category of posts here at Dark Twins, I had this card in mind—along with all of the many associations I now make with it. There are many and sundry reasons its appearance in my Shadow Stack is perfectly appropriate, and I will explore some of them here.

This is one of the only cards in the entire tarot that is likely to be just as unwelcome, if not even more so, than The Tower itself. This card is generally held to be really, really bad news.

It also fits together very well with Ace of Disks, this chapter’s Sun Card—especially in terms of the deeper themes related to materialism that I explored above. Based on the Qabalistic formula for tarot interpretation, the 10s all represent the sephirah of Malkuth, “Kingdom”—the sephirah most directly related to the physical world. Since swords are the suit of the intellect, of rationality and analysis, this combination suggests the end result of the process of “analyzing the material world” in the most strictly rational sense. Is it a coincidence that the end result carries the title of “Ruin” in Crowley’s Thoth tarot?

Likewise, the more traditional version of this card, from the Smith-Colman deck, shows a human figure laying dead on the ground, pierced with 10 swords; and, indeed, if we were to physically dissect a living person for the purposes of analysis, we would inevitably kill them in the process.

If we were to do so, would this suggest the person had never been alive to begin with? Certainly not. Likewise (although by now, we all know I’m biased in this regard), I would maintain that the end result of carrying the process of scientific analysis of the material world all the way to its most thorough conclusions is indeed likely to end with a fully mechanistic and lifeless view of the universe—which, of course, does not mean there is no life there to be found. It just means we will never measure it with our physical instruments.

One reason this card is so fitting for my Shadow Stack is this: Although I clearly do not identify personally as an atheist, the reality is that by a broader definition of the term, I actually am one. Many people don’t realize that the term “atheist” actually describes a much wider variety of perspectives than it seems. When I use the term, I tend to use it largely as a synonym for philosophical physicalists, who hold that there is nothing to the universe except matter—that consciousness is thus an illusion, which is a position that ends up in the negation of the existence of free will. I do this mainly because among the people I have known in life who describe themselves as “atheists,” virtually all of them have very clearly and explicitly expressed to me that such was their viewpoint. No room for spirit at all, nor even for bona fide consciousness as a thing-in-itself; just material building blocks, all interacting with one another in a purely mechanistic way.

In truth, I would be a type of atheist by virtue of the fact that I do not believe in a personal God who exists outside of and presides over the universe. More accurately, my view would likely be considered pantheistic, but some schools of thought consider that a non-religious and thus basically atheist position.

Honestly, it’s kind of gnarly that words like this, which we all seem to take for granted and use in such offhand ways, sometimes have “fuzzier,” more indistinct meanings if you really want to analyze them to death.

Many people consider atheism to be a view of negation. This is evident in the very structure of the word, from the root atheos, or a-”without” + theos-”god.” Further, this inclination is shown in the historic pathway that has carved out a place for atheism in our world today: We once appealed to God to explain just about everything, and even as our developing understanding of physical science began to “cut away” our previous theistic explanations for phenomena, religious holdouts still clung to God as the explanatory force for whatever was yet unexplained; nowadays, we have found (or at least soundly theorized) purely physical explanations for so many things that we largely conclude we’ve got it pretty much all figured out. Since the overwhelming pattern, again and again, has been that theistic explanations have given way to rational, physical ones, logic would suggest that ultimately, there is nothing but matter to explain everything in the world. Through the process of negation, we have thus done away with God.

However, logic also dictates that just because we’ve identified physical processes for most phenomena does not mean we have positively ruled out the existence of God; indeed, if God is purely spiritual in nature, we can never disprove the existence of God or the spirit world. It is a logical impossibility to use material means to prove or disprove an immaterial reality. From this perspective, atheism is not necessarily a negation even if that’s the process most people use to arrive at such a conclusion: Instead, the physicalist/materialist philosophical stance is very much a positive belief that matter is all that exists.

At this point, we are splitting hairs so finely that it may not even matter one way or the other. In effect, what matters most is what can be proven, and the physical laws that govern our world seem to hold the most sway even if, somehow, we can squeeze God in between the particles somewhere. So has matter won over spirit? In a sense, that’s largely in the eye of the beholder. In the most ultimate sense, spirit and matter seem to be in perpetual check, though the materialist perspective certainly seems more feasible to a growing number of people, and arguing with the processes science has uncovered seems foolhardy.

In short, this is the foundation of postmodernism—the philosophical perspective that since science has successfully displaced God as an explanatory narrative for what goes on in the universe, God himself might as well be dead too. Postmodernism basically says that there is no single, grand, unifying narrative inherent in the world since the predictive power of physical science has proven so effective. This is why I described it as a double-edged sword, and the end result depends largely on where we choose to place our focus:

On the one hand, it seems to have slain the very essence of meaning itself by positing that meaning is not inherent in the universe. This is largely what people like Nietzsche and Evola seem to have been reacting to, and it’s the main aspect of Nietzsche’s nihilism that most people readily understand and relate to. However, this really only corresponds to one phase of nihilism—in other words, to what is known as “passive nihilism,” which says: “God is dead—now what?”

What fewer people understand is that there is a corresponding active phase of nihilism: Once God and his/its meaning have been negated, rather than being left with a resulting emptiness, we are in fact empowered to fill in that gap with whatever meaning we choose. That’s actually an empowering perspective—for those willing to rise to such an occasion. However, it suggests that our job is then to put ourselves into the gap left behind after putting God to death.

This entire path of inquiry fits very well with both the 10 of Swords—as a symbolic representation of science and philosophy as truth processes, or ways of analyzing the world to better understand it—but also to the Ace of Disks as the root of matter, because what these processes have ultimately done is served to focus our attention on the root of matter itself.

Is that the beginning and the end of meaning?

Should it be?

Art Chad recently released a video that explores the intersection of postmodernism and materialism in a capitalist context, highlighting the ways in which it has resulted in many of us waging war on our very own bodies by framing the recent “Black Pill” phenomenon as a symptom of an ideological disease. Most interestingly, near the end, he issues a call for us to take ourselves less seriously and embrace our imperfections, to the backdrop of the phrase “THIS IS A SPIRITUAL WAR.”

Can we leverage a conscious relationship with narrative to remedy this? Is this one reason we might still need something akin to spirituality no matter what material science manages to explain for us?

This question lays at the heart of the “spiritual war.” Some people can’t live with the questions this leaves unanswered, and cope by regressing to God as an explanation. Others bravely say they have no need of God at all, nor of any inherent meaning or shared universal narrative other than whatever light science can shed on the world. Others still recognize the strength of this latter position, but see some possible gaps remaining in the human soul (even if the soul is understood only in a figurative sense) by leaving everything in the hands of matter to explain. Do we need to replace God with some kind of meaning, even if we recognize that it’s merely a “placeholder” that makes life seem more manageable to us?

I still say that’s debatable, and I still think there are some ways in which, even with the rational understanding of the world science has brought us, we can perhaps better navigate history by giving our human desire for narrative an agreed upon pathway for expression, even if we do so with the acknowledgement that it’s just a made-up story. As human beings, I sometimes think we do better even with made-up stories, and that the main harm comes from forgetting that we did, indeed, make the stories up.

All of this makes me think of the “saga” of my relationship, over time, with the demon Vine. I told this long and interesting story in the post My Cousin Vine, although the story didn’t end where I left it in that post. It also ties into the Shadow Card for this chapter, 10 of Swords, in some interesting ways. For example, in his own tarot deck, The Tarot of Ceremonial Magick, Lon Milo DuQuette assigned the demon Vine (along with the demon Paimon—recognizable to fans of the horror film Hereditary) as an attribution to the 10 of Swords.

Anyway, one of the main relevant aspects of my ongoing and developing relationship with Vine is that I never really “believed” in his independent existence. At most, it was occasionally a somewhat open question, but there was also always the underlying understanding that on some level, Vine was an aspect of my own unconscious mind. His persona was a “screen” onto which I projected various disowned aspects of my own being, and so long as I continued to disown those aspects of my being, he nonetheless remained firmly outside of my control. Working with such spirits very much involves a suspension of disbelief more so than an active belief.

As I described in My Cousin Vine, I came to see Vine as a “vessel” for my own Shadow traits, which I identified as of the writing of that post as those connected with toxic masculinity and patriarchal violence—a legacy I unavoidably inherited as a white male raised in the modern West by a father very much controlled by those same demons. I identified a very close relationship between Vine and my own alcoholism, which I was lucid enough to connect to the Shadow traits I just mentioned.

At the end of the post, I allude to finally overcoming Vine “by the power of Thoth-Hermes.” What I didn’t go into very deeply was just what that meant. Thoth-Hermes is a magic(k)al personification of the forces connected in alchemy with the principle of Mercury: In other words, spirit as the unifying principle between the body and the soul. Just as I had identified Vine as a personification of disowned aspects of my own personality, so was Thoth-Hermes a personification of my power to take charge of that narrative to “command the demon Vine.” All of this exists in a “fuzzy” sort of state in which one relates to figures such as gods and demons as if they existed objectively, but without losing sight of the fact that they actually represent deep inner aspects of the self. It’s ironic, but the best way to come to a full understanding of just how deeply such entities are rooted in the self is to first allow them to “split off” and relate to them as an “other,” only to trace their roots back into our very own hearts. This is something that can only be fully understood by indulging the process and giving it a try.

I bring all of this up because it occurs to me that in its own dual-aspected nature, postmodernism is very “Mercurial” in its own right, embodying elements of both the “solve” and the “coagula” sides of alchemy. For this reason, I agree with those who hold that Evola was a sub-par occultist. Why? Because, even though he himself gave plenty of lip service to both the active and passive aspects of nihilism, he went on to bemoan the horrible consequences of the postmodern world he saw as so bereft of meaning, and he refused to adequately take ownership of his own agency in shaping meaning for himself. In his chapters regarding politics, he yearns for a bygone world that still held a place for a true and sovereign political monarchy, and fails to recognize that that royal power never disappeared from the world—it simply shifted its locus into the heart of the individual, receding from its more explicit outer expression. It was always there for him to claim—and he utterly failed to do so even though he clearly outlines such an imperative in his chapters about nihilism. It’s pretty absurd, really.

The part I didn’t cover in My Cousin Vine was the final necessary step I needed to take in order to fully integrate him: I had succeeded in identifying the negative traits he represented, but it wasn’t until I identified the positive and useful traits he also represented that I was able to fully integrate him, command him, and overcome the alcoholism he also represented:

As a “King” of Hell, he represented a level of personal sovereignty that I was too weighed down by self-doubt to claim for myself. Likewise, as an anthropomorphic lion, he represented the raw power and the courage I could not identify as my own. In other words, he wasn’t a fully “bad guy.” If you read the post and understand the life circumstances that prevailed when I first ritually bound him to myself, you will see that I was living by some fundamentally disempowering beliefs. I was the victim of my own limited ideas of myself. I was giving my personal agency over to other people and groups in my life, and likewise, Vine continued to haunt my subjectivity until I started to claim that same power for myself.

This reflects the stance necessary in order for humanity to move successfully from either its religiously dogmatic phase or its materially dogmatic phase to its utterly magical phase wherein, perceiving the divinity in ourselves, we can safely perceive it in the world around us in a way that leaves us empowered and dwelling in a truly sacred relationship with the world around us.

But really, none of this is particularly new or special…so don’t take my Word for it.