All of a sudden, it feels very strange returning to the Inner Tarot Revolution series of posts. When I last wrote an entry for this series, I felt a very strong sense of urgency to finish the last few posts because the series—which doubles as a magic(k)al working—has been going on for so long and that has weighed so heavily on my mind. Actually, I recently learned that this is far more than a mere subjective experience on my part. It’s so reliable that the science of psychology has a name for it. The Zeigarnik Effect— named after Bluma Zeigarnik, the psychologist who first identified and described it—is the human mind’s tendency to fixate on unfinished tasks. Unfinished tasks really do sit there in our memory banks, and if they hang around there for long enough, the effect upon recalling an unfinished task can be really draining. This is an aspect of the deep relationship between the conscious and subconscious minds that I first learned about indirectly in a book about magic(k); in a magic(k)al context, the focus was on the idea that when we create servitors or talismans, they continue to draw on our “life force” until we banish, reabsorb, or otherwise dispel them. A related idea was that if we had too many different talismans or servitors working for us all at once, it would have a deleterious effect on our vitality. I strongly suspect this idea is related in some way to the Zeigarnik Effect: We can only handle having so many different “plates” spinning at once in the back of our heads, so-to-speak.

Anyway, I surprised myself a bit by suddenly feeling inspired to wrap up my ongoing work involving Zelda instead, with the trio of posts comprising my most recent work since Chapter 35 of this series. I’m glad I did that, because not only did it clear out my World of Ruin “buffer,” but it unexpectedly brought all other aspects of my overall work surrounding the Word of Hermekate into greater clarity. I sharpened and focused several key ideas that I’d been having difficulty articulating before, and I have a much better appreciation for how everything I’ve been working on for the past 8 years fits together. Little did I know, Part 3 of the Zelda series would end up basically serving as the “capstone” of the wider pyramid of all of that work. The next major set of steps in my work are now clear. This series is no longer available.

And consequently, the pressure to finish Inner Tarot Revolutions feels much less urgent because of just how effectively the Magic(k)al Theory of Zelda series cleared out my cluttered psyche.

As an added bonus, I had been feeling pretty stuck trying to figure out just what I wanted to write concerning this chapter’s Sun and Shadow cards—but inspiration struck partway through writing the Zelda series. Everything works out if you just let it, ya know?

At any rate, the coolest part of all of this is that a number of the issues connected with the Word of Hermekate that came into focus through the Zelda series just happen to fit really well with the cards for today’s post. The basic issue in question is one of balance—of that oh-so-thin line between hitting a bullseye and pushing things too far.

I’ve touched on some of these concerns in previous posts, but the main inflection point I’m referring to here is the Aeonic nature of the Word of Hermekate, and by extension, two of its dichotomies:

The dichotomy of Eastern and Western spiritual/magic(k)al perspectives

The dichotomy between the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path

The main realization I’ve come to is that all of these issues are really just different facets of the same thing, and this one thing is such a deep part of the Word of Hermekate that it’s reflected even in the very structure of the Word itself (being the name of a compound deity linking Hermes and Hekate—two deities with deeply contrasting qualities).

Resolving all of these more abstract intellectual discrepancies has come hand-in-hand with ironing out some deeply visceral internal conflicts of my own, as well.

One of the themes that has come out as a highlight of many of my recent posts has been my relationship with The Temple of Set in particular and the Left Hand Path more generally. There’s a lot that I’ve written over the last few months that has been born of a great deal of personal disappointment and frustration on my part. As I’ve confided, I’ve had to do a lot of work to sort out my personal hurt feelings from my true ideals in order to make sure all of this work that I’ve done doesn’t simply boil down to acting out my own resentments. I am quite satisfied that it goes far deeper than that.

Much of this has come to the forefront of my mind over the last day or so, because yesterday was White Lotus Day—commemorating the death of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky on May 8th, 1891. As a former worker for The Theosophical Society in America, such a day has strong resonance for me. As it turns out, this ties in with the other issues under discussion here. I wrote a post for my original blog, Hermekate, back in 2020 and republished it here at Dark Twins on April Fool’s Day last year: Tribute to A Trickster. In it, I lay out a cannabis-inspired “insight” I had while visiting Krotona Institute of Theosophy in Ojai, CA as part of my participation in Partners In Theosophy, the mentorship program through which I was once being groomed for future Theosophical leadership. The basic gist of the theory was that Blavatsky had seen plenty of trauma throughout her life, especially in her world travels, and that maybe the Masters were personae she conjured up—largely as a trauma response—to cope with that trauma and to lend legitimacy to her work. Since I wrote that post, I’ve even had some insight regarding Dissociative Identity Disorder, because the pattern that Morya and Koot Hoomi showed of being stalwart defenders of H.P.B. has a lot in common with the protective function of the “alters” developed by people with D.I.D.

Though such a theory would likely deeply offend many of my former Theosophical fellows, it’s one I crafted from the very bottom of my heart, because I have a lot of sympathy for H.P.B.—especially if my theories hold a grain of truth. People give Blavatsky a lot of flak, but honestly, even if she was a “charlatan” in this sense, it’s not like that would make her an outlier in the world of the occult; the general consensus is that the Golden Dawn’s “Secret Chiefs” weren’t real, either, and even Anton LaVey—revered by his admirers for his cutting intellectual skepticism—told more than a few of his own tall tales. It seems to come with the territory.

As I mentioned in Part Three of my recent Zelda series, the term “Left Hand Path” was introduced into the Western occult lexicon by Blavatsky herself, and it was during my time with The Theosophical Society that I remember first encountering the term (though in truth, it was The Satanic Bible). I also mentioned in that post, as well as Tribute to a Trickster, that one of the major driving forces behind my cutting ties with the Society was the cognitive dissonance stemming from the fact that, although the term was not a positive one at all in the Theosophical context, I honestly felt like it might fit me.

To better understand this dynamic, one must be familiar with the fact that as a spiritual system of belief, Theosophy has very strong roots in bhakti yoga, a path essentially defined by its emphasis on devotion to one’s guru, spiritual teacher and/or God, and which puts great value on selflessness and on serving others. This is such an important aspect of Theosophical philosophy that a rather perverse situation prevails wherein many Theosophists almost seem to be in competition with one another about just how selfless they can be. People go very far out of their way to display their selflessness and willingness to serve others in order to be recognized as more advanced on the spiritual path. In Theosophical circles, being selfless is a flex, and the implication that you’re selfish is a matter of abject shame. In these circles, the Left Hand Path, by contrast, is defined largely by its emphasis on selfishness and egotism (which is not too far-removed from the way adherents of the modern LHP happily define the path). I’ve known this to go so far that in some online discussion forums, it was not uncommon for some dramatic types to “throw shade” by implying someone was an evil “black magician” because they showed a little bit too much arrogance or pride.

I happened to notice, all throughout my time in the Society, that I was very often preoccupied with myself—with understanding myself, with my own personal growth and development, and with making progress on my own spiritual path. These were tendencies that, in Theosophical circles, were often very explicitly listed as personal vices. This was the basic root of the shame I carried deep within, even as the leaders of the Society put me up on stages behind podiums to give talks for them that were praised by members all across the country. When we would hold our annual Summer National Gatherings at the Olcott Center in Wheaton, visitors from out of town would go out of their way to find me and shake the hand of the young man about whom they had heard so much; and yet I was always keenly aware of just how much my attention was drawn inward, toward my own experiences and to making my own way through the world.

I felt this tension so deeply that I occasionally tried to write poems on the theme of “the gravity of the self,” because to me, it was as though I tried and tried to expand my attention outward to be of greater service to others, but I simply could not reach “escape velocity” so as to break free from the tremendous “weight” pulling my focus back toward myself. That metaphor stayed with me for years, even after I cut ties with the organization and moved to Norway.

Apart from the way these tendencies might be viewed through a specifically Theosophical lens, I did not see these patterns as a bad thing, per se; this was not an avaricious sort of self-centeredness. I didn’t enjoy taking from others, being a burden, or causing harm. In a lot of ways, I kept my attention to myself because I recognized that at the end of the day, my self was pretty much the one thing in the world I actually had any control over, and thus I had a responsibility to myself. This wasn’t egotism or shallow pride.

But I felt there was no way to tell that to a dedicated Theosophist; the language of such leading lights as Annie Besant, Krishnamurti, C.W. Leadbeater and even Blavatsky herself was very clear: Such traits were a moral failing.

Although I had an early interest in some of the more incredible metaphysical aspects of Theosophy that later became mainstays of New Age thought—stuff like clairvoyant visions of auras, thought forms, and devas (angels)—the major point of connection that I had with Theosophical teachings was the concept of Initiation. Most people understand the word “initiation” in the context of rites of passage like girls celebrating their Sweet 16, or the sacrament of marriage, or induction into a group like a street gang or a college fraternity or sorority. However, there is a deeper meaning of the term that has more to do with spiritual and psychological development—which is held to occur across a series of recognizable stages. This is something with which Theosophy is deeply concerned, though as I mentioned above, the Theosophical emphasis is on a devotional mode of the same; Initiation as presented in Theosophical teachings is heavily dependent on one’s connection with a guru figure such as a Master of the Wisdom akin to the men Blavatsky claimed to serve.

Initiation was a concern of mine since long before I became a Theosophist, stemming all the way from my high school days when my “spirit guides,” Ilyas and Rose, hinted that it lay at the very center of my life’s purpose; as such, it remained an interest of mine even after I left the T.S. and began my self-Initiatory magic(k)al work. I studied the work of Paul Foster Case, who, like Blavatsky, also claimed to be in touch with a Master—”Master R.,” or Count Ragoczy—St. Germaine himself. Such teachings still didn’t feel like the best fit in the world, but I hadn’t found anything better. Although he defied the Theosophical mold of Initiation in the sense that he advocated the practice of Ceremonial Magic(k), as well as in his (heavily veiled) references to sexual alchemy—both the kind of practice that was sharply proscribed by Theosophists—he wasn’t all that different in his moral stances regarding selflessness and service to others.

It wasn’t until I came across the writings of Don Webb and Dr. Stephen Flowers of the Temple of Set that I seemed to have found “the sweet spot:” People who proudly and emphatically operated under the banner of the Left Hand Path, but in a way that emphasized a very similar conception of Initiation to what my prior studies had embodied. The focus was shamelessly placed upon the Self, but in a way that recognized deeper principles at work than sheer narcissism, greed, or lust for power; one that embraced carnal pleasures, but also insisted that the practitioner not allow these to overwhelm one’s capacity for self-control. This was a synthesis of obvious and deep esoteric wisdom with common-sense, no-nonsense pragmatism that eagerly embraced science where even Theosophists often seemed timid about straying too far from the comforting framework of whimsical spiritual idealism. It was more concerned with making the most of one’s life in the here and now, while Theosophy was apt to emphasize thinking in terms of rewards one might not reap until after their physical death, or even in their next incarnation.

I sensed that such an approach would be really beneficial for me.

After reading a few books and getting an essay published (under my birth name) in Questing SET Digest, I eagerly put in an application to join Temple of Set. A series of unfortunate personal circumstances saw my application put on hold for a year, then for three years, and before long, I felt an absolute sense of despair at the fact that my bids to join the organization were so unsuccessful—and, of course, there was the Word of Hermekate: As far as I could see, there was no other esoteric group in the world with quite the same view of Initiatory grades as the Temple of Set—one that held the grade of Magus as something attainable enough that it was considered to be well within the reach of at least a few different people at the same time. I knew from the depths of my soul that the Word of Hermekate was the specific manifestation of my Initiatory life purpose as whispered to me by Rose and Ilyas (see When They Talk Back). If anyone could help me fulfill my purpose—in Thelemic terms, to do my True Will—it would be them.

After my application was put on hold the second time, the prospect of remaining “exiled” for 3 entire years seemed unbearable, since the Word of Hermekate had already been revealed to me; it was at that point that I first began to read the writing on the wall and to suspect that my fate just may be to carry my Word all alone.

It was a heartbreaking possibility, but the flip side is that it was also an honorable one: If such was my lot, it could only be because I actually had the strength within me to carry the Task myself…and honestly, to carry it alone would be far more in keeping with the spirit of the Left Hand Path than to wait around for help.

However, there was one more obstacle: As the years wore on and I gained more experience and knowledge of the modern Left Hand Path, it began to occur to me that, at least based on the more stringent forms of LHP philosophy I was coming to understand…even then, I remained a round peg trying to fit into a square hole. I wasn’t seeing the LHP in quite the same way as most of the people around me in the community, and I began to feel like I was trying to wrangle the LHP itself into something that it wasn’t.

It wasn’t quite my “sweet spot” after all, and I would have to just take the initiative and carve such a spot out for myself. It wasn’t long before I understood that this was actually one of the main purposes of my Word…I just had a very difficult time coming to terms with the personal sacrifice it would require me to make, along with the doubts I carried about my ability to meet the challenges involved.

But let’s do cards.

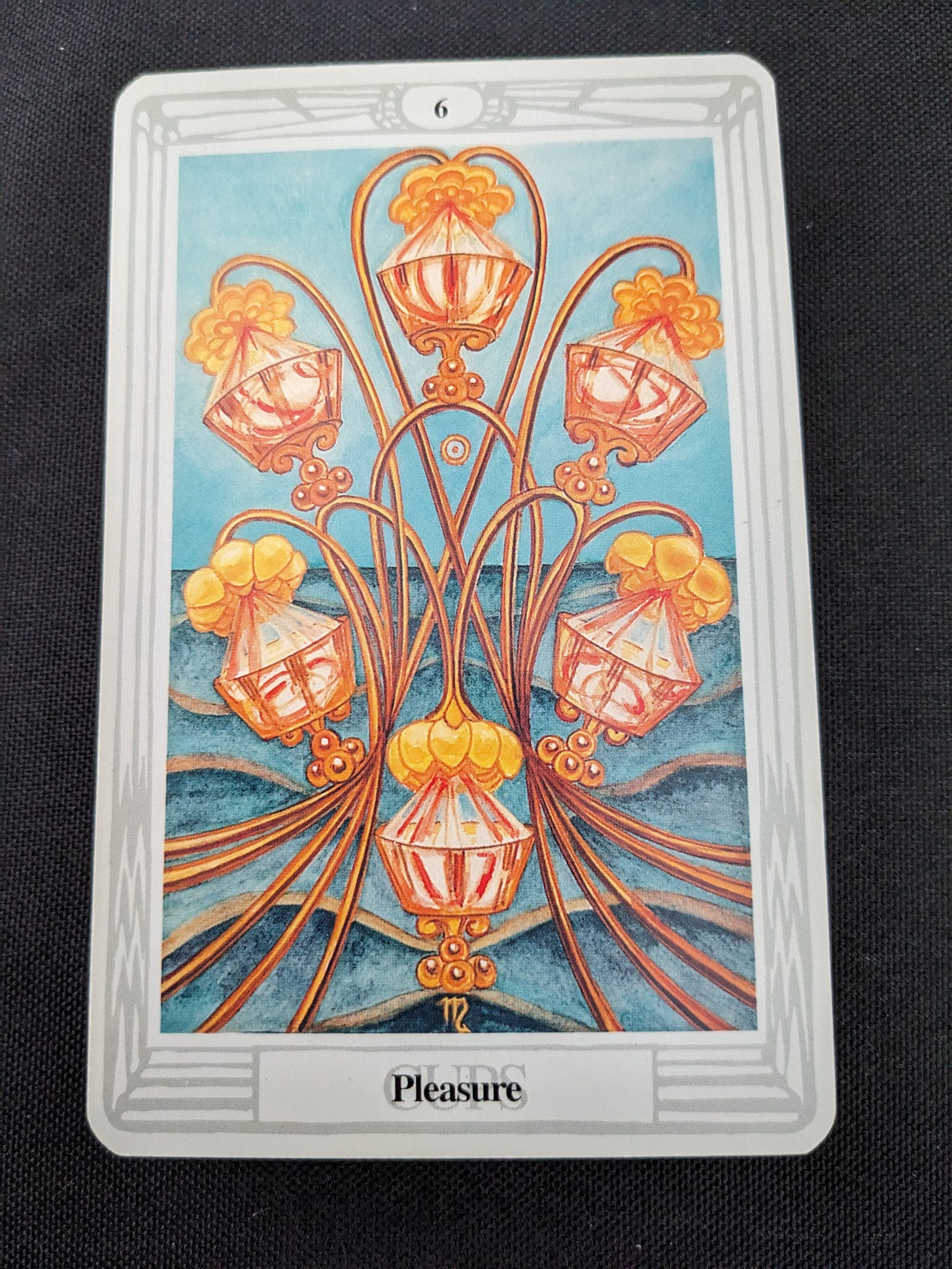

Top/Sun Card

Now here’s a “sweet spot” if ever there was one: The Six of Cups, or “Pleasure.” I’m just going to jump right into what Lon Milo DuQuette has to say about it in Understanding Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot:

Balance returns to the suit as the Six of Cups, Pleasure, finds a most delightful home in Tiphareth, the sphere of the Sun. The Four and Five of Cups seem like bad dreams (probably brought on by consuming too much rich food and wine), and we now awaken to the giddy realization that we are the card that is the direct reflection of the Ace of Cups on the Tree of Life. The Sun is outrageously happy to be in Tiphareth and shines with double warmth and pleasantness on the sensuous and fun-loving sign of Scorpio. If this is the first card you draw in a tarot reading, you may want to stop right there and quit while you’re ahead. This is a terrific card.

p. 231

Sounds pretty good to me. How does it sound to you? Sounds like there’s nothing here to be concerned about at all.

However, that would depend quite a bit on one’s perspective. From the strictest viewpoint of modern Left Hand Path philosophy, there are a couple of problems painted into the picture here.

For one, Tiphareth is the sphere of the Sun; for the typical Western Ceremonial magician, that’s just fine, but from the Left Hand Path perspective, the dark cloak of night and its shadows are preferable to the light cast by the Sun. As The Book of Coming Forth By Night itself states:

But speak to me at night, for the sky then becomes an entrance and not a barrier. And those who call me the Prince of Darkness do me no dishonor.

The Temple of Set Vol. II

p. 37

On the Left Hand Path, if you’re going to be dealing with the Qabalah at all, you’d more likely be dealing with the Tree of Death than the Tree of Life, working with the Qlippah corresponding with Tiphareth rather than the sephirah itself.

However, Michael Aquino seemed to very much share in Anton Szandor LaVey’s utter distaste for the Qabalah as a whole—he rejected it wholesale, all but making this, too, explicit in The Book of Coming Forth By Night; so in the Temple of Set, you’d much more likely be working with the system of Nine Angles than the Tree of Life or The Tree of Death.

Furthermore, in the system of Nine Angles, the number 6—the number of Tiphareth on the Tree of Life—is not favorable at all even though it’s highly revered as the sixth sephirah in Ceremonial Magic(k). To Aquino, 6 represented not “balance” and stability, but rather “stasis,” suggesting a principle such as stagnation rather than something with a more appealing connotation such as stillness. He strongly disliked this, instead preferring the activity and dynamism suggested by the number 9.

As we can see, Michael Aquino was rather insistent on taking most of the conventional wisdom associated with Ceremonial Magic(k) and turning it on its head.

Such is prerogative of the Left Hand Path.

As The Book of Coming Forth By Night also states:

Now let the Setian shun all recitation, for the text of another is an affront to the Self.

p. 37

In other words, the Left Hand Path urges one to leave such established paths as the Tree of Life behind, instead to boldly explore other Initiatory frameworks, all in an effort to touch the deeper reaches of the Self in the most unmediated, authentic way possible.

These are some examples of the extremes of the Left Hand Path that I never really felt were important. I feel just fine and dandy framing ideas in terms of the Tree of Life; I really don’t feel oppressed by it. Instead, I feel liberated, because the Tree of Life is a framework understood by far more numerous people, which means I have a robust language for communicating with a greater number of people about spiritual ideas.

According to the conventions established by Aquino, if you’re following some external framework like the Tree of Life, you’re walking the Right Hand Path, not the Left Hand Path: In this sense, the Right Hand Path describes any traditional, well-worn, more popular path—especially one connected with an established religious tradition—while the Left Hand Path describes deviating from the Right Hand Path and doing your own thing.

Similarly, there are other basic aspects of Michael Aquino’s definition of the Left Hand Path that I never could fully embrace because I flat-out disagree with him. For example, Aquino held that the Left Hand Path seeks to develop the principle of Isolate Intelligence; that is, not only does it seek to further define the individual in their own right, but goes so far as to state that the spiritual goal of the Left Hand Path practitioner is that of non-union from the rest of the universe, from nature. This is to be pursued to the most extreme extent possible: That is, the objective of self-deification is held to mean that when the black magician succeeds in such a goal, they then exist entirely in their own, completely unique “subjective universe” completely apart from the “objective universe,” or the world that is shared with others. When such a person dies physically, the operative idea here is that the magician enters their own entirely separate universe. This is all in complete contradistinction from the Right Hand Path, where rather than separation, the objective is union with “Godhead” or some deity.

Along this same vein, the Egyptian neter Set, whose “Gift” to us is our human level of intelligence and consciousness, is said to be the one “non-natural” neter, and that his Gift to humanity makes our intelligence similarly “non-natural” in essence.

Honestly, I never fully accepted that ideas like this are even feasible or likely. They just don’t really seem all that sensible to me.

Part of the reason for this is because I always liked Blavatsky’s definition of the term “natural:” In her view, everything that exists is technically natural, and there is no such thing as “supernatural” phenomena. Even completely artificial contraptions created by human beings are technically natural. Ghosts and spirits aren’t “supernatural,” they’re just natural in a different sense from physical beings. Nothing that exists at all can be thought of as being beyond the scope of nature. To her, the very word “nature” covers everything.

Clearly, Aquino’s definition of the word “nature” was something different from this—he drew his lines differently (in point of fact, he drew lines at all, whereas in this regard, Blavatsky drew none). And I suppose that’s just great for those who see things similarly…but the way Aquino saw these things just seems arbitrary and needlessly complicated to me.

Similarly, the extent to which Aquino seemed to push for Setians to follow unique and unconventional personal paths seemed just as arbitrary, and even subject to a certain amount of contradiction. I mean, insofar as a person wants to walk a completely idiosyncratic and unique path, sure…go for it…but to go so far as to almost insist on doing it “the hard way” just seems almost obsessive. For instance, if the Tree of Life works as a model, it doesn’t seem to me that there’s any good reason not to work with it. This tendency reaches the point where it almost feels like this “pure” definition of the LHP takes things so far that it kind of wedges people into making life much harder for themselves than they really need to.

Though to be fair, on the Left Hand Path, there can be good reasons for doing so intentionally.

Nevermind the contradiction involved: We can weave uniqueness and idiosyncrasy into our definition of the LHP to such a degree that we declare anyone following the Qabalah to be technically walking the RHP, and then we can make up our own quirky little system like The Nine Angles…except that now, that’s just another established tradition. Now that’s a Right Hand Path. And you’ve got to admit, there’s a certain irony to writing an inspired text that says that “the text of another is an affront to the self,” and then starting a club where all the members constantly cite that text. Like…hellooooooo?

So I guess my point is that if you really want to carry this all the way to the most anal-retentive conclusions, you can try to do that, but it eventually starts to prove futile. At the end of the day, even people on the Left Hand Path are, in many ways, walking both the Left Hand Path and the Right Hand Path. It’s unavoidable.

All of this comes full circle to the matter of “Eastern” vs. “Western” spirituality. According to Michael Aquino, part of the definition of a Word (in the sense of a Magus’ Word) is that it introduces a relatively new concept into the Aeonic balance; as far as the idea of “Eastern/Western synthesis” goes, there’s hardly anything “new” about that. Crowley did the same thing with Thelema, incorporating elements from Buddhism just as readily as from Hermeticism. Similarly, Theosophy was its own brand of East/West synthesis. So in that regard, saying that Hermekate involves an ‘East/West synthesis” is nothing new. That’s one particular problem I’ve been puzzling over for years now.

However, there is one sense in which this term holds true which does carry some fairly novel implications that speak to some of the conflicts and contradictions I’ve addressed above.

Like the Left Hand Path, one defining feature of Western philosophy and culture is its emphasis on individualism. The Western person seeks to emphasize and express their own uniqueness as an individual, and in a sense, this is the core principle that runs through everything I’ve been describing about the Left Hand Path above. This is, in fact, the basis for the convention that traditions flowing from the Church of Satan and/or the Temple of Set constitute the “Western Left Hand Path”—that is still what many of the LHP’s leading figures call the path to this day.

In contrast, what modern people know as “Eastern” cultures are different from Western cultures in the fact that they are more communitarian and collectivist. The sense of self and the personal identity are held, in Eastern cultures, to be less important than the well-being of one’s family, community, and culture. Individuals from Eastern cultures are much more apt to sacrifice their personal goals and desires for the sake of the well-being of the groups to which they belong; people may give up on pursuing a personal interest like becoming an artist because they can make more money to share with their families by focusing on a different career, for example. An individual from such a culture may actually give more money away to their family members than they keep for themselves, if they keep any at all.

This difference in emphasis is the root source of the tendency I described in the introductory section of this post for Theosophy to emphasize selflessness—this was, in large part, a product of its deep connection to religions from Eastern cultures.

While these tendencies are largely a form of shorthand, they do basically hold true. However, some aspects of this tendency are blown out of proportion. For example, from studying Michael Aquino’s writings, it seems that he was often operating on some fairly shallow and oversimplified assumptions regarding some forms of Eastern spirituality such as Buddhism, that he may have been fairly ignorant of the more individualistic aspects of some Eastern practices, and also—again—that he may have focused overmuch on strict interpretations of some terms. I’ve pointed it out before: He was simply an extremely rational thinker, who did very often see things in stark black-and-white terms where this was not always necessary, or even all that helpful.

On the other side of things—the scientific and rational side—as the grand project of Western science advances, we’re learning a lot about the nature of the world (and the nature of human beings) that is beginning to erode the stricter definitions of the Left Hand Path, and indeed, the very notion of Western individualism itself that Aquino seemed to hold sacred.

For example, venerating the principle of the individual is well and good—and as I’ll explore in the next section, there are situations where it’s actually vital—but what are the actual boundaries of the self? Where does the self end and the world around us—or the ideological frameworks supporting and informing us—begin? Does the self even have clear borders? How many of our deeply cherished beliefs and ideas are really “ours?” To what extent are we products of our environment? Is the “self,” in fact, anything more than a fancy electric “illusion” in a fully deterministic meat-brain, as the recently-deceased Daniel Dennett held? The notion of a truly distinct, sharply-definable self grows thinner and thinner with every passing day as science teaches us more and more about what it means to be human.

This leads to the emerging Philosophy of Co-Becoming: A nascent school of thought that appears to be seeking to synthesize a working balance combining various elements of “Eastern” and “Western” models of the self. From the article linked at the beginning of this paragraph:

Song goes on to observe that “while modernization and Westernization in the past 150 years have infused the narrative of liberal values of individualism, free choice and self-determination into the global public and political discourse, people in the East Asian societies continue to be deeply shaped by the time-honored values and practices in their personal, familial, social and even political lives. They have been constantly oscillating between the world of modernity and that of ancient cultures.”

Convivialism tries to split the difference. “Legitimate individuation,” another movement manifesto reads, “allows each individual to develop their individuality to the fullest by developing his or her capacities, power to be and act, without harming that of others, with a view toward equal freedom. Unlike individualism, where the individual cares only for oneself, thus leading to the struggle of all against all, the principle of legitimate individuation recognizes only the value of individuals who affirm their singularity in respect for their interdependence with others and with nature.” As Song notes, they even assign subjectivity to other species in their thinking.

That, right there, is the essence of what I mean when I say that the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path can be synthesized, that they are not so different from one another, and that similarly, the future of the so-called “Left Hand Path” involves doing away with the very distinction of “Western Left Hand Path” (which is why, of late, I have been using the term “Modern Left Hand Path” instead). This is especially true since the LHP literally takes its name from Eastern esoteric systems, which renders the distinction of “Western Left Hand Path” a veritable absurdity (albeit one very typical of Western arrogance and presumption, to be fair). In short, we live in an increasingly interconnected, cosmopolitan world of integration and globalization. There’s little use fighting it. This is the future (and honestly, the present).

East and West—and likewise, the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path—are merging. A new synthesis is being born. This is what will ultimately lead, esoterically, to the emergence of N’Aton. The Aeon of Set will ultimately give way to the Aeon of Ma’at. However—ironically—the particular form of collective consciousness that will characterize the Aeon of Ma’at will ultimately be dependent on the continued thriving of the Aeon of Set, which will in fact be its cornerstone. The two Aeons need one another, and this is an important aspect of the the Word of Hermekate. Every other principle I can name as a part of the Word ultimately connects back to this.

This chapter’s Shadow Card holds some of the keys to just why and how that is.

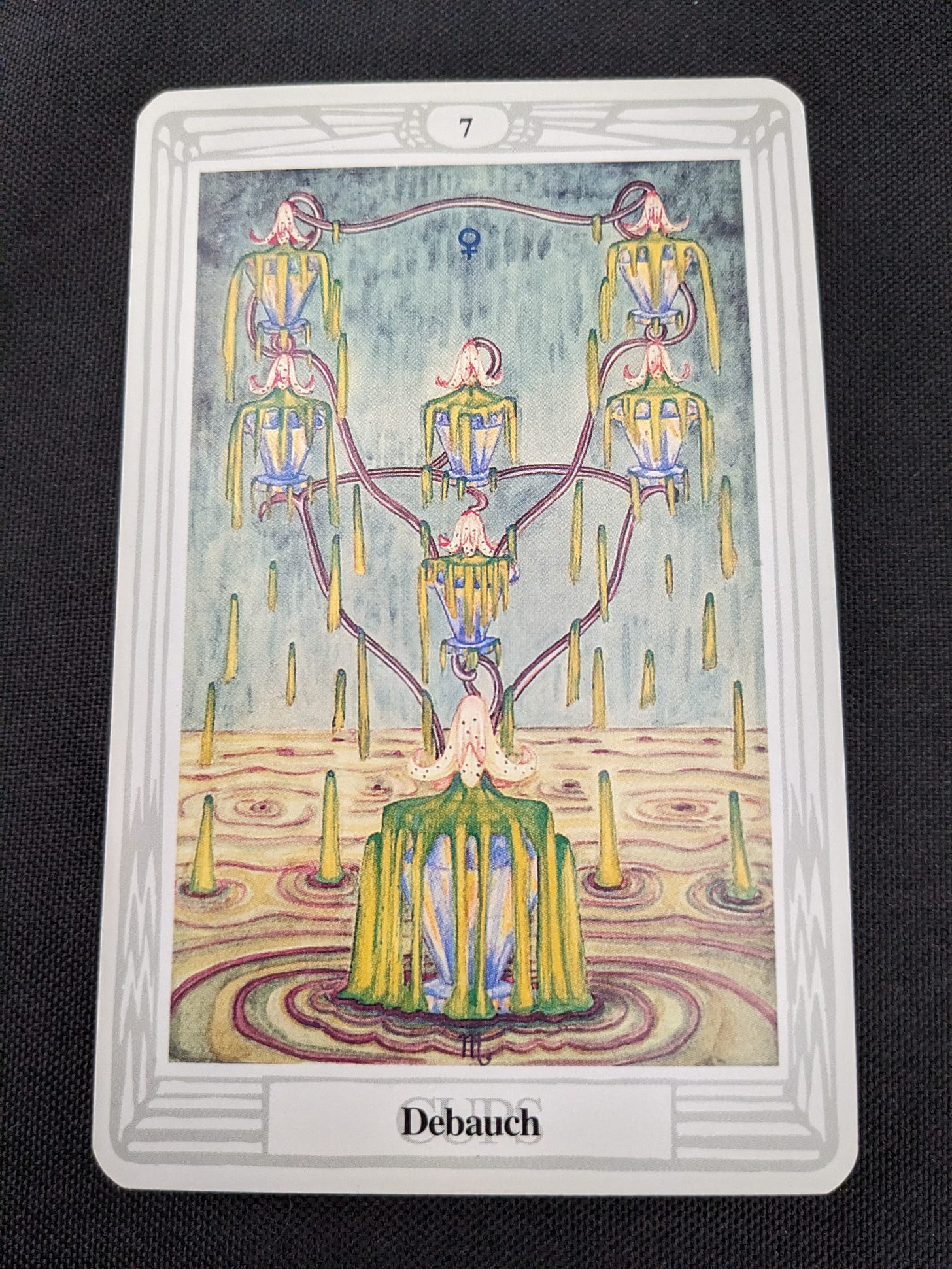

Shadow Card

Both the Sun Card and Shadow Card for this chapter are next-door neighbors. How about that? Taken together, they illustrate a somewhat important concept: That the distance between the height of sustainable bliss and toxic excess can be as short as the distance between the numbers 6 and 7. While one immediately follows the other in numeric succession, the two resulting cards could not be more different from one another in their overall tone.

According to DuQuette:

Just look at this card—if you can. Yuck! What happened to all that great Cup stuff higher up on the Tree of Life? Doesn’t sexy Venus like to show off in sexy Scorpio? She does. She likes to show off everywhere! Venus, however, is not well dignified in Scorpio and often embarrasses herself when she visits.

p. 233

I know the feeling all too well, especially owing to the state of mind I was in when I first began writing Dark Twins.

He continues:

This card seems like the next logical step in the Abundance, Luxury, Disappointment sequence. Three martinis is abundantly enough; four is just the luxury of showing off; five is disappointing because you’re not getting high any more, you’re just getting smashed. But after seven—oh dear! The Seven of Cups is a stumbling dash to the lavatory just moments after you thought you were being irresistible to an attractive stranger.

p. 234

While I focused on more general, collective themes in the Sun Card section, I’ll be circling back to some more personal issues here in the Shadow Card section—in keeping with my closing comments above about the importance of the Aeon of Set.

The connecting theme between both cards—aside from the suit of Cups—is the sign of Scorpio, which DuQuette described above as “sexy Scorpio.” As it turns out, this provides some hints about the deeper levels of my internal conflict while working for The Theosophical Society—and my reasons for leaving. Simply put, it all revolves around sexual trauma.

Around the time I began volunteering at the Olcott Center in Wheaton, I was living in a household where there were both sexual and emotional abuse going on. Frankly, I probably wouldn’t have thrown myself so emphatically head-first into my Theosophical work if that were not the case; although I didn’t realize it at the time—because I honestly didn’t even recognize the sexual abuse in said living situation for what it was. Dedicating so much of my time, energy, and attention to The Theosophical Society was basically my own personal version of running away to join the circus.

One of the main reasons the situation was so opaque to me at the time was the fact that my abuser was a woman—my aunt—and it took me many years to realize that she was, in fact, a perpetrator. Due to the common understanding of gender roles and the relative rarity of sexual abuse perpetrated by women, I instead thought I was the sole perpetrator. Honestly, as the saying goes, “hell is murky,” and there was…untoward behavior on my part as well. However, as I have since learned in therapy and support groups, my reactions to the situation were actually normal for what was basically a textbook case of abuse by a female caregiver…and that all happened to me many years after the more central childhood traumas that shaped me as a person.

It took years of healing and processing for me to realize that this points to one of the main reasons my drive to turn inward and focus on myself during my Theosophical years was not at all a moral failing, and to why, in some cases, immersion in environments that stress such self-denial can actually be extremely unhealthy for certain people:

I was traumatized, and I needed very much to work on myself. My very broken, very wounded self needed attention. I needed to heal. And frankly? All that emphasis on “spiritual self-denial” was getting in the way of that. It’s evident in the fact that, as I prepared to leave the Society and move to an entirely different country, I completely fell apart and descended into a maelstrom of substance abuse and acting out my sexual trauma that was very characteristic of the energy of the 7 of Cups: Debauch.

As I look back, I see strong connections between my trauma and my attraction to the Left Hand Path. Frankly, it was even more pronounced in some ways many years before the sexual abuse: I refer with great distaste nowadays to various aspects of Anton LaVey’s personality and philosophy, and similarly reject the marked focus for many on the Left Hand Path on the cultivation of personal power over others; however, there was a much younger, much more bitter, much more angry, and much more wounded version of myself who was all about that shit. That’s why I have such little patience for it now: Because frankly, it’s something I’ve worked hard to outgrow and put behind me.

I’ve noticed certain…tendencies and patterns…in others on the Left Hand Path, as well. I’ve had a few conversations with friends who have observed it: There seems to be a noticeable connection between trauma and a personal inclination toward the Left Hand Path.

It makes sense on many levels. As I observed, albeit in a different context, in Part Three of the Zelda series: The Yiga Clan in Breath of the Wild are so obsessed with power because it’s something they lack. Do you know where that insight came from?

It came from personal experience. I’ve been there. Similarly, I recognize that for a long time, the main reason the Left Hand Path was so attractive to me that I thought it was a matter of life and death to be accepted into the Temple of Set is because my own sense of Self—my deep core—was in a weakened, injured state. I was magnetically drawn to a path defined by principles such as personal sovereignty and self-discipline because those were things I lacked, aspects of myself that were underdeveloped…and while I won’t go so far as to suggest that this sums up the attraction of everyone to the LHP, I can confidently surmise that it’s a pretty common pattern.

For example, Anton LaVey seems like a pretty obvious example of someone who had a fairly rough early life and some unhealed traumas of his own. The same frankly goes for Aleister Crowley. Such grand egotism is well-known as a trauma response: It’s a compensation for a deep inner emptiness that seeks to protect its own considerable fragility by puffing itself up so as to appear more threatening.

I wrote much more openly about a lot of this stuff once upon a time. In fact, writing Dark Twins was one of the most important aspects of processing the trauma, and there was a time when it felt good and validating for it all to be witnessed by readers; however—as I’ve mentioned so many times it’s almost sickening by now—I was in a fairly “rare” state of mind when I started writing this blog, and from my more healed (and more sober) perspective today, I don’t feel it’s as necessary to have all that trauma hanging out in the open. It may actually do more harm than good at this point. It felt appropriate, at the time, to share it and that was an important step in the healing, but now that it’s done, I’m giving very careful thought to how—and if—I’ll allow it all to be visible again.

This relationship between trauma—especially sexual trauma—and the Left Hand Path actually seems to be encoded into its very mythic structure in some ways. After all, Set is known, in some versions of the myth of The Contendings of Horus and Set, for sodomizing his nephew.

Certain traumas—especially sexual ones—have a very distinct effect on the ego. They either shatter it beyond repair, leading to extremely pathological behaviors and compulsions that never really heal, or—in the best of circumstances—they cast a long, dark shadow over one’s life that, nonetheless, leads to a very unique sort of opportunity for growth if one can succeed in healing. Trauma can, in some cases, lead to an even stronger core and a much wiser, more resilient, and more compassionate self.

I feel very deeply that this may be the very essence of the Left Hand Path for many people—and that while there is a limit to how much healing some people can do (which is part of how we get some figures like the LaVeys and Crowleys of the world)—it might be a worthwhile goal for many people who walk the Left Hand Path to actually spend a bit less time focusing on developing power and “control” over their lives, and a bit more time focusing on actually healing. At least, that reflects my own experience.

At the beginning of this series, I was in the throes of addiction and trauma, and now—close to 11 months sober and nearing the end of this series—that urgency I once felt to find a place among my “fellows” on the Left Hand Path has all but subsided. It truly doesn’t matter to me anymore whether other people accept me or acknowledge my ideas as being especially compatible with an LHP ethos. In fact, I see a lot on the Left Hand Path that just makes me shake my head. As I said near the closing of my most recent post, I’m making peace with the idea that I likely don’t really want to fit in with many who walk the path. They have a lot of healing to do (provided they ever actually get around to it), and in the meantime, I’m done with that chapter of my life and looking toward moving into fearlessly lowering my own walls and getting more involved with others. I have nothing to hide from anymore.

Regardless, all of this highlights some important aspects of the Aeon of Set: While I can’t say everyone drawn to it is necessarily driven to it by trauma, it nonetheless occupies a very important niche of the spiritual ecosystem, especially in a world like ours where certain forms of personal trauma are on the rise. Sure, history has been rough before, in some ways that make the modern world pale in comparison—but we have a stronger tendency to survive nowadays, while society imposes strange new psychological pressures that are historically unprecedented and with which our biological systems have not evolved to cope well.

We live in interesting times.

As such, if we hope to see the Aeon of Ma’at in its full flowering…we need the intrepid tenacity of the Aeon of Set to get there.